the Met, Munich, La Scala, and Pesaro’s

prestigious Rossini Opera Festival). He

ranks among today’s most renowned

bel

canto

interpreters, and has performed

seven Rossini operas. “When I was 19,” he

recalls, “my teacher gave me

The Barber of

Seville

and it just fit. I like to think that if

I’d been born in Rossini’s time, he would

have liked to write for my voice. I say that

because the roles I sing were written for

specific tenors. I can look at one of those

roles and think, ‘Since they sang this, I

probably could sing it.’”

In portraying Ramiro, Brownlee finds

his greatest challenge is capturing what

the prince is unable to express outright.

When disguised as his own valet, “he’s

saying how upset he is, and what he

doesn’t like, but he doesn’t get to do what

his rank and power would otherwise allow

him to do until Act Two. For all of Act

One, he has to sustain that frustration of

not being able to let himself go.”

All the singing in

Cinderella

is

formidably difficult, but Leonard actually

doesn’t mind that Rossini saves the

heroine’s big showpiece until the very

end. “I think it’s great! There’s something

about the way the entire piece is written

that allows the role to flow very nicely

vocally.” Rossini intersperses Cinderella’s

sweetly lyrical moments with a lot of

very florid singing. “In some ways it’s

like a vocal massage throughout the

show. Whenever you change the range,

the dynamics, the rhythm, you’re also

allowing the flexibility to continue, which

is always very helpful—and by the time

you get to the end of the show, you’re

thoroughly warmed up!”

Ramiro’s big aria also comes fairly

late in the opera, when he’s declaring that

he’ll search through woods and rivers to

win the girl he loves. Here Brownlee can

lavish on his audience the remarkable

florid ability for which he’s celebrated.

But he also loves the aria’s quiet, soulful

middle verse, “where he talks about how

Cinderella is a treasure. He must find her,

he says, because of her

goodness.

That’s the

moment where he gets a chance to break

out and show who he is—his real colors.

It’s an emotion he’s never felt before.”

There’s a freshness and a delight in

Rossini’s version of the famous fairytale

that make

Cinderella

enchanting onstage.

Whether listeners are experiencing it

for the first time or the umpteenth, says

Brownlee, “they can connect with that

story and feel like they had a fulfilled

evening seeing the opera. When you see

Cinderella and the goodness she feels, you

want her to win.”

Lyric Opera presentation generously

made possible by

Margot and Josef

Lakonishok, The Nelson Cornelius

Production Endowment Fund,

and

PowerShares QQQ.

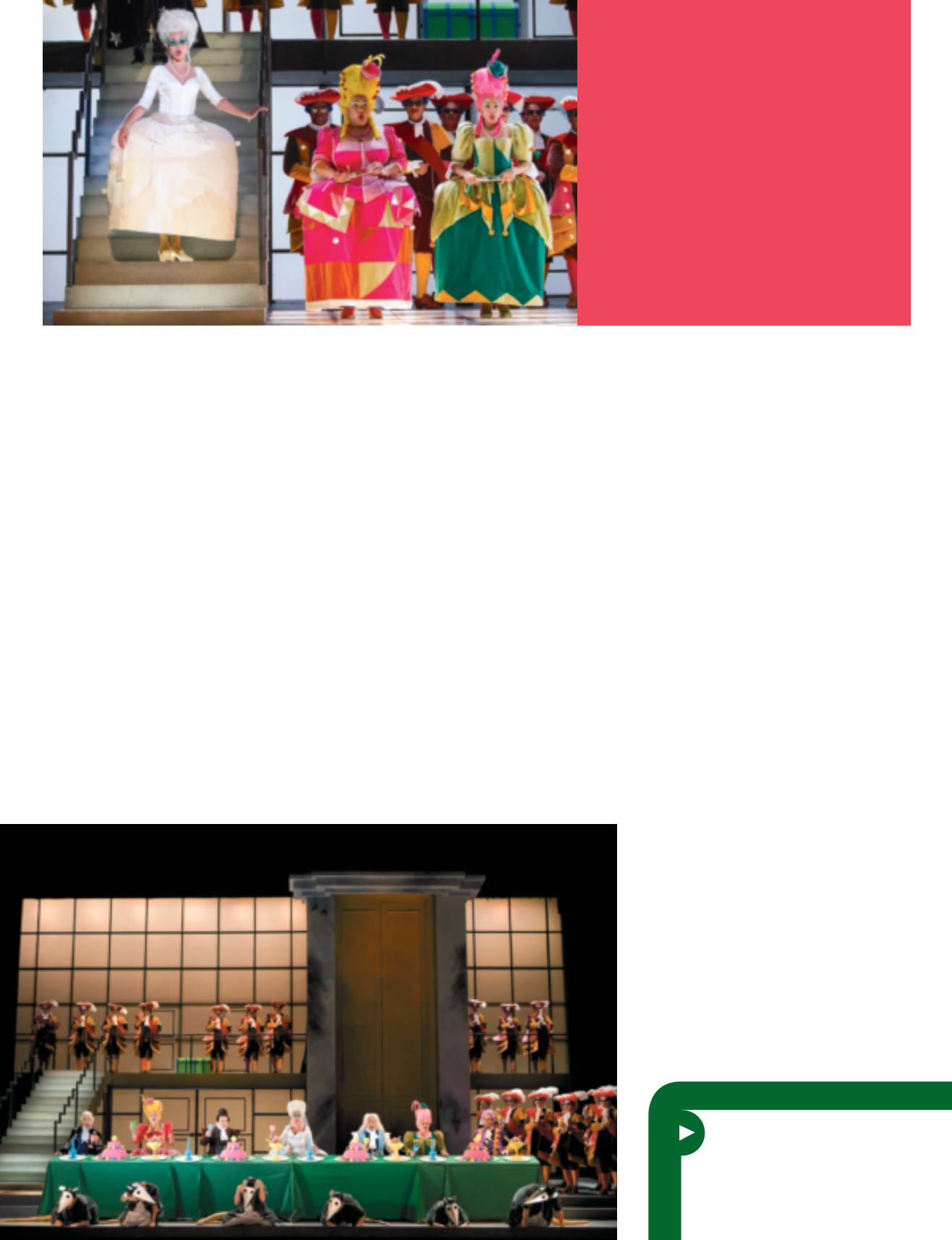

Coproduction of

Houston Grand Opera, Welsh National

Opera, GranThéâtre del Liceu, and Grand

Theatre de Genéve.

See the lighter side of Cinderella in a “Patter Up!” video interview with Isabel Leonard at lyricopera.org/Cinderella.“I think we’re all a little

cynical nowwhen we think

about hope. But there’s

something to it when

someone really perseveres

through their hope, and I

think that’s a beautiful idea.”

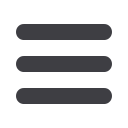

SCOTTSUCHMAN (WASHINGTONNATIONALOPERA)

BRETTCOOMER (WELSHNATIONALOPERA)