4

Bird Lives

By George L. Starks, Jr., Ph.D.

Charles Parker, Jr., was born on August 29, 1920 in

Kansas City, Kansas

and grew up across the river in the fertile musical

environment of Kansas City, Missouri. This was the wide open Kansas City

of the Tom Pendergast Machine during which nightlife flourished. In the

city’s African American neighborhood, so did the music of Bennie Moten,

Andy Kirk, and Walter Page. Count Basie from Red Bank, New Jersey, Lester

Young from Woodville, Mississippi, and Mary Lou Williams from Pittsburgh,

Pennsylvania took up residence in Kansas City. Theirs was the Kansas City of

all-night jam sessions, riff-based blues, spontaneous “head” arrangements,

and blues shouters - big voiced vocalists who sang the blues.

This was Charlie Parker’s Kansas City. He absorbed it all, particularly the

lessons of residents like tenor saxophonist Young and alto saxophonist

Buster Smith. From guitarist Efferge Ware he learned about chords and their

relationships. Here, he played in the bands of Jay McShann, Tommy Douglas,

and Harlan Leonard. During a road trip with the McShann band, Parker

retrieved a chicken which had been struck and killed by the car in which he

was riding, a retrieval that earned him the moniker “Yardbird.”

But Kansas City could not contain Yardbird. It was in New York during the

1940s that Bird truly spread his wings. He was the perfect example of a prime

axiom of jazz − one must find one’s own voice. It was in Harlem after-hours

sessions at Monroe’s Uptown House and Minton’s Playhouse that he, along

with participants like Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Christian, Thelonious Monk, and

Kenny Clarke, found nurturing environments for the development of a new

music known as

bebop

.

Parker’s innovations defined bebop and what came to be called

modern

jazz

. Though rooted in tradition, the chord changes were nevertheless

dramatic. On many levels the music became more complex. Parker’s music

demonstrated great harmonic acuity. He altered chords, developed new

progressions, and substituted chords with substitutes! In pre-composed

melodies and in improvisations, his work featured melodic twists and turns

that were completely

new. Front line instruments

interacted with rhythm

sections in new and

dramatic ways; pianists

comped and drummers

played polyrhythmically.

He brought a new timbre

to the alto saxophone

and other saxophonists

followed his lead. Most

of all, the rhythmic

sophistication that he

brought to his music was

unlike that of anyone who had preceded him.

The musical tradition of jazz has always been responsive to, and reflective

of, the socio-cultural environment in which it is situated. Parker’s music gave

voice to much of what was felt in this country during the 1940s. This was

particularly true of the African American community. Participation in the

war effort led the black community to expect fundamental change in that

community’s position in American society. New times demanded new artistic

expression, and bebop was a part of that expression.

Parker’s contributions have been recognized in numerous ways. One of the

first was Birdland, a jazz club in New York City named in his honor, which

opened in 1949. Also, there is an annual Charlie Parker Jazz Festival in his

adopted hometown of New York City, and a Charlie Parker Memorial

sculpture in Kansas City. Largely as a result of the role it played in the

development of bebop, Minton’s Playhouse is listed on the National Register

of Historic Places.

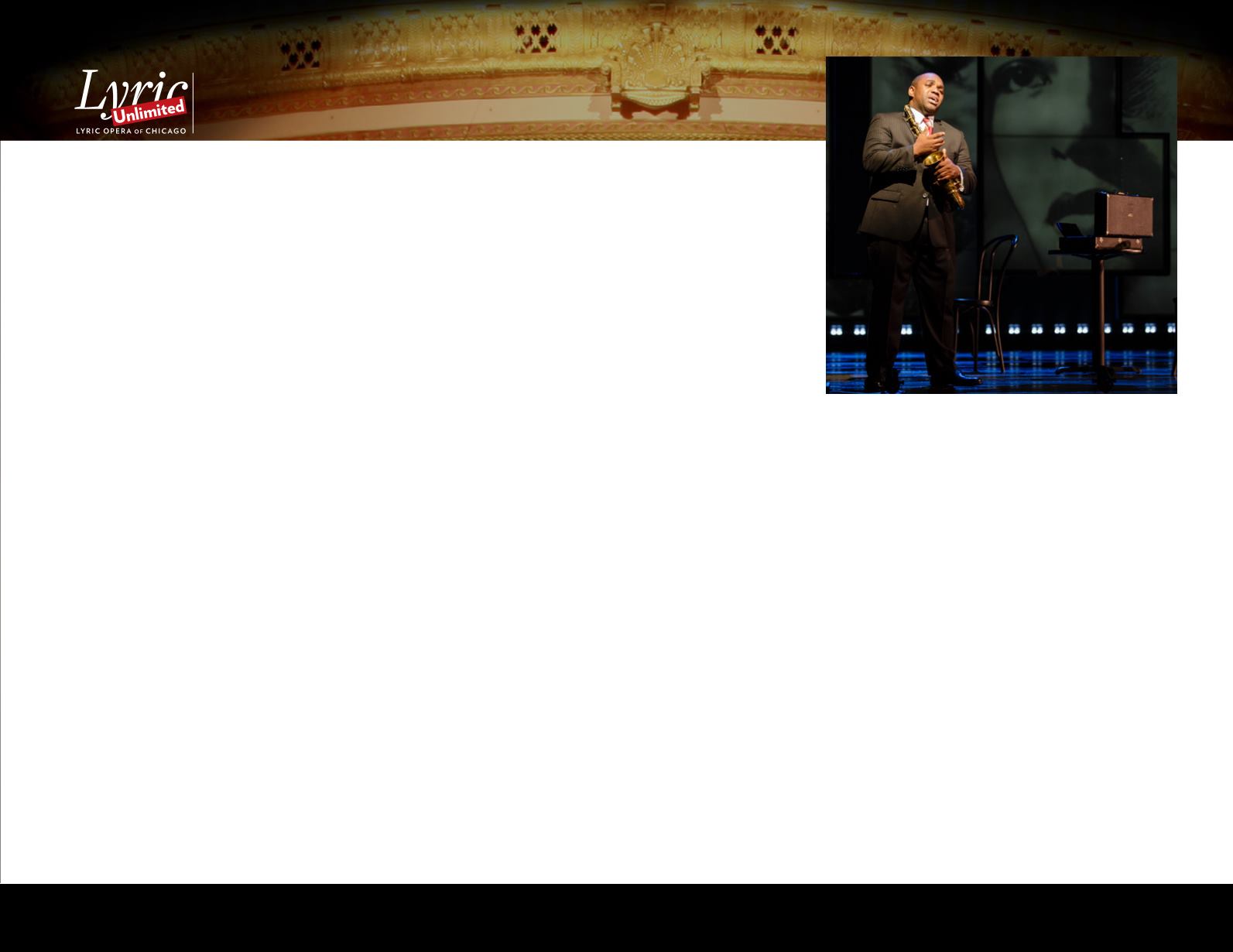

Dead at the age of 34, Parker had an enormous influence that has

extended far beyond his lifetime. Much in the sense that Parker found

his voice by studying the music of Lester Young, Buster Smith, and Chu

< > CONTENTSc. Dominic M. Mercier - Opera Philadelphia