O P E R A N O T E S | L Y R I C O P E R A O F C H I C A G O

January 28 - February 24, 2017

|

31

the other hand, in that role, traditionally

assigned to coloratura voices, the composer

was eager to have not just dazzling technical

facility but also a certain dramatic color that

Pasta could provide in spades.

Pasta was a new kind of prima donna

– one of three women (Spain’s Maria

Malibran and Germany’s Wilhelmine

Schröder-Devrient were the others) who

together brought into being the decidedly

new idea of an operatic leading lady as a

“singing actress.” Pasta, by all accounts,

exuded dignity and regality onstage, with

the innate gift of expressive depth that

bespoke a true

tragedienne.

Yes, previous

leading ladies in bel canto repertoire had

displayed similarly refined musicianship

and vocal dexterity. Pasta, however, was

also utterly committed to the nuances of

drama and communicated overwhelming

theatrical presence. She simply

embodied

Norma and the other heroines in her

repertoire, including no fewer than 20 that

she premiered during her illustrious career.

The actress Fanny Kemble, who

heard all the greats in London for some

six decades, remarked of them that “above

them all, Pasta appears to me pre-eminent

for musical and dramatic genius – alone and

unapproached – the muse of tragic song.”

Perhaps the most famous quote related

to an opera singer during the entire 19th

century was in response to Pasta. Apparently

she kept her expressive powers to the end,

even when her voice was in tatters. One

of her greatest successors, Malibran’s sister

Pauline Viardot, attended the next-to-last

performance of Pasta’s career, in London

in 1850. Overwhelmed by the artistry she

had just witnessed, she declared that “like

the ‘Cenacolo’ [Last Supper] of da Vinci - a

wreck of a picture, but the picture is the

greatest in the world.”

Opposite Pasta in the first

Norma

were

three dazzling stars: Giulia Grisi (Adalgisa),

the Joan Sutherland of her day, soon to

become internationally celebrated in all the

great diva roles of bel canto, Norma included;

Domenico Donzelli, Italy’s first dramatic

tenor, with reportedly a marvelously dark-

toned, ultra-masculine instrument; and

Vincenzo Negrini (Oroveso), a magnificent

bass-baritone who no doubt would have

become one of the legendary figures of

Italian singing had heart disease not claimed

him at the age of only 35.

With all the vocal glory lavished on

it, and the glory of the Bellini score itself,

it seems completely bewildering that the

opening night of

Norma

at La Scala proved

decidedly unsuccessful. Why did it fail to

achieve a triumph? Bellini thought this

might have been due to the machinations

of a faction supported by money from

the rich mistress of a rival composer. But

Norma

did triumph thereafter, with nearly

40 performances in that first Milan season

alone. It also made it to America within

ten years, and arrived at the Metropolitan

Opera in 1890, during the company’s

seventh season, with a great Wagnerian,

Lilli Lehmann, in the title role.

Norma

very quickly became

the

piece

against which great sopranos measured

themselves. It was also the Bellini opera that

other composers most admired. One, in fact,

was Richard Wagner, who truly worshipped

Bellini. Six years after the premiere, he

conducted it himself; he wrote that “of all

Bellini’s creations, it’s

Norma

that unites

the richest flow of melody with the deepest

glow of truth.”

The principal men have their grand-

scale moments – Oroveso in his two scenes

with the male chorus, Pollione in his

exhilarating entrance scene – but the opera

truly belongs to the two women. Adalgisa

(written for the soprano Grisi, but generally

taken today by high mezzo-sopranos)

actually often sings in Norma’s range, and

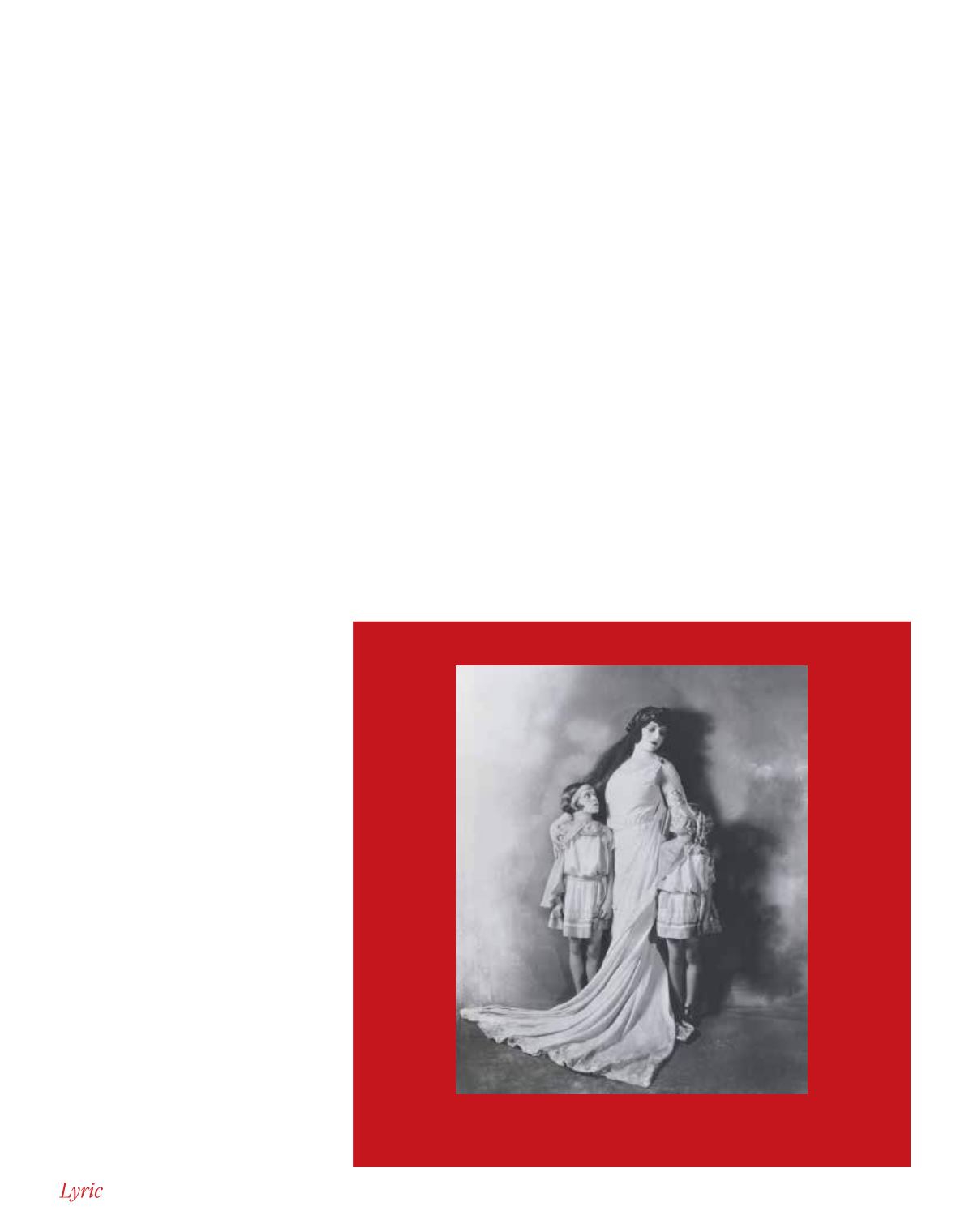

HERMAN MISHKIN/METROPOLITAN OPERA ARCHIVES

Rosa Ponselle, the definitive Norma of her generation,

at the Metropolitan Opera, 1927.