L Y R I C O P E R A O F C H I C A G O

November 1 - 30, 2017

|

17

conducting actually work? Davis cites recent

performances of Mahler’s

Symphony No. 7

with the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester

Berlin: “They hadn’t played the piece in at

least eight years. I started rehearsing four

days before the concert and had probably

a few hours more than you’d have with

North American or British orchestras, who

are incredibly quick. European orchestras

are very good, but it takes them longer

sometimes to figure things out.” Whenever

rehearsal time is limited, “early in the

rehearsal period you have to establish certain

stylistic or rhythmic concerns that are going

to be endemic throughout the piece. If you

fix those quickly, it will carry over into the

rest of the rehearsals. How you play the

dotted rhythms in the Mahler 7 – that kind

of thing.”

Whether a Beethoven symphony, a

Wagner opera, or a Strauss tone poem,

the privilege of leading great masterpieces

continues to thrill Davis immeasurably.

“This music is just so fantastic. But it’s not

a great sense of power that a conductor feels

– more often, it’s a great sense of terror!

The fact is that there’s all this extraordinary

repertoire that

needs

a conductor, this vast

treasure-house of music covering many

centuries.”

How does Davis explain what he and

his conducting colleagues

do

on the podium?

“The basic thing you’re doing is helping

musicians play together! But that, of course,

is just the beginning. If you play a Mozart

symphony, probably a great orchestra could

play it by itself, but it wouldn’t necessarily

add up musically. I’ve always been one of

those people who say that it’s all there on

the page – but obviously, you’re going to

interpret

one way or another. There are

infinite different details, and decisions that

can be made in different ways: how loud do

you want the strings to be in relation to the

brass? How much time do you take at the

end of a particular phrase? It’s incredibly

subtle sometimes, but those things really

make a difference.”

Whereas an orchestra concert can be

prepared in just a couple of days, preparing

an opera performance is different. With

Die

Walküre

, “we’ll start staging rehearsals and

then I’ll get into orchestra readings, which

are spread over a couple of weeks. Then we

bring everyone together for the first time in

the

Sitzprobe

[literally “sitting rehearsal,”

traditionally with singers onstage at music

stands and the orchestra in the pit]. It’s

very advantageous to have this time to

put everything together. That’s true of any

opera production, particularly something as

complex and long as the

Ring

operas.”

The initial days of the rehearsal

period don’t generally find Davis working

musically with the cast. The tradition in

opera is that everyone comes to the initial

piano rehearsals and goes through staging,

“and it’s only after it’s all coming together

dramatically that I’ll have music rehearsals

with the singers. That’s after they’re done

worrying about what they’re doing onstage

– we can then solidify the musical concept.

I think most conductors would agree with

me: in a long staging period, even the best

singers tend to put the music secondary, in

relation to what they’re trying to achieve

dramatically. For me, you need that time

when everything becomes musically really

solid, in the latter stages of preparation.”

An essential element that separates

Davis’s work on orchestral concerts from

opera performances is that “in opera you’re

dealing with the setting of text, so you have

to know the libretto very thoroughly. When

I’m conducting a Wagner opera, that aspect

involves a long period of preparation for

me.” For

Walküre

Davis started working

two years ahead. Some orchestral pieces, too,

certainly demand very extensive advance

work – for example, any Mahler symphony,

which Davis will generally begin working

on a year before the performance (“I’ve

done all the Mahler symphonies, but not as

often as you might imagine”). Even if it’s a

work that he’s conducted fairly frequently,

he always returns to the score ahead of

time to reconsider details, keeping in mind

Toscanini’s famous comment, “I sleep with

the ‘

Eroica’ Symphony

under my pillow!”

It’s important to Sir Andrew never to take

anything for granted in his music-making:

“I just did Mahler 7 in Melbourne in

March. The last time I’d done it was at least

20 years before, and it was like a new piece.”

Returning to certain works gives

a conductor a chance to rethink an

interpretation, something Davis invariably

relishes. “There will be things that had

totally escaped you previously that you now

suddenly discover, one hopes! With Mahler,

I think just the psychological fact of having

Don Giovanni

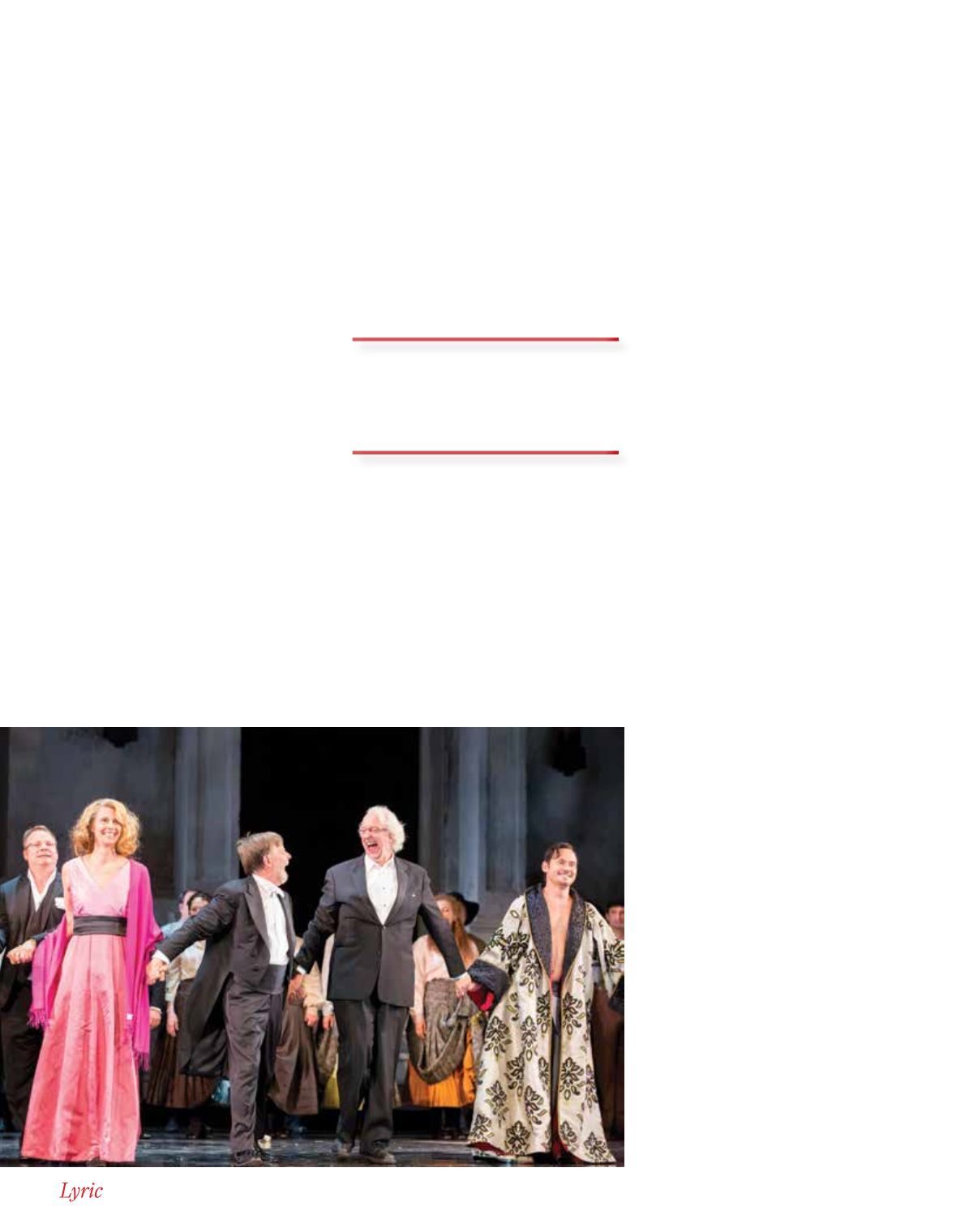

curtain call, 2014: left to right, set designer Walt Spangler,

costume designer Ana Kuzmanic, Sir Andrew Davis, director Robert Falls,

baritone Mariusz Kwiecień (title role).

TODD ROSENBERG

Whereas an orchestra concert

can be prepared in just a couple

of days, preparing an opera

performance is different.