4

This Dangerous Role:

Carmen

, Women and Society

When Bizet’s

Carmen

premiered in Paris in 1875,

it shocked audiences with its plot, its music—and

especially its heroine.

Carmen

was performed at the Opéra-

Comique, a theater known for light, family-friendly fare. Ludovic Halévy, who

coauthored the libretto, described how director Adolphe de Leuven reacted

to the suggestion of an opera based on the novella by Prosper Mérimée.

“He actually interrupted me,” Halévy recalled, “‘Mérimée’s

Carmen

! Isn’t

she killed by her lover? And these bandits, gypsies, and girls working in a

cigar factory! At the Opéra-Comique! You’ll frighten our audience away.’”

(Halévy) The character Carmen is brazen, opinionated and manipulative.

She is a gypsy and an independent woman earning her own living. Her

willingness to use her sensuality to get what she wanted scandalized the

Opéra-Comique’s middle class patrons.

In Latin, the word

carmen

means song, verse or enchantment. It’s a fitting

name for Bizet’s heroine, who seems to cast a spell over men. After their

first encounter, Don José remarks, “If there really are witches/she’s certainly

one.” One of the charges frequently leveled against gypsies was that they

dabbled in the dark arts of sorcery and magic. Gypsies were outsiders

in Spain, living on the fringes of mainstream society; throughout Europe,

discriminatory laws were passed against them for centuries. They were

stereotyped as a people ruled by instinct, less civilized than lighter-skinned

Europeans. In a similar vein, women in the 19th century were described as

less rational than men, susceptible to being overcome by their emotions.

As a woman and a gypsy, then, Carmen was already established as a

temptress, not to be trusted.

It is significant that Carmen works in the cigarette factory. She is unmarried

and independent, earning her own income. In Bizet’s time, a woman’s

proper place was thought to be in the home. A woman went from her

father’s home to her husband’s when she married. An independent woman

was suspect. Carmen openly relishes her freedom: In Act II she sings, “The

open sky, the wandering life,/the whole wide world your domain;/for

law your own free will,/and above all, that intoxicating thing:/Freedom!

Freedom!” The men of

Carmen

, by contrast, speak to the women in terms of

coercion and possession, whether it is the soldiers insisting to Micaëla “You’ll

stay!” as she protests, “Indeed, I won’t!” or Don José agonizing over Carmen:

“For you had only to appear,/only to throw a glance my way,/to take

possession of my whole being,/O my Carmen,/and I was your chattel! I shall

compel you/to bow to the destiny/that links your fate with mine!” Carmen

is unwilling to sacrifice her freedom for love; Don José is willing to murder his

beloved, rather than allow her to assert her independence.

When he pitched the idea for

Carmen

to the skeptical director of the

Opéra-Comique, librettist Halévy sang the praises of a character he and

Meilhac had added to Mérimée’s story: one “perfectly in keeping with the

style of the opéra-comique…a young girl of great chastity and innocence.”

(Halévy ) He was alluding, of course, to Micaëla, Carmen’s foil and Don

José’s intended. Carmen’s use of her sensuality to get what she needs is

contrasted to Micaëla’s sweetness and submission. Demure and proper,

Micaëla represents the Victorian ideal of womanhood—home, family

< > CONTENTSBy Maia Morgan

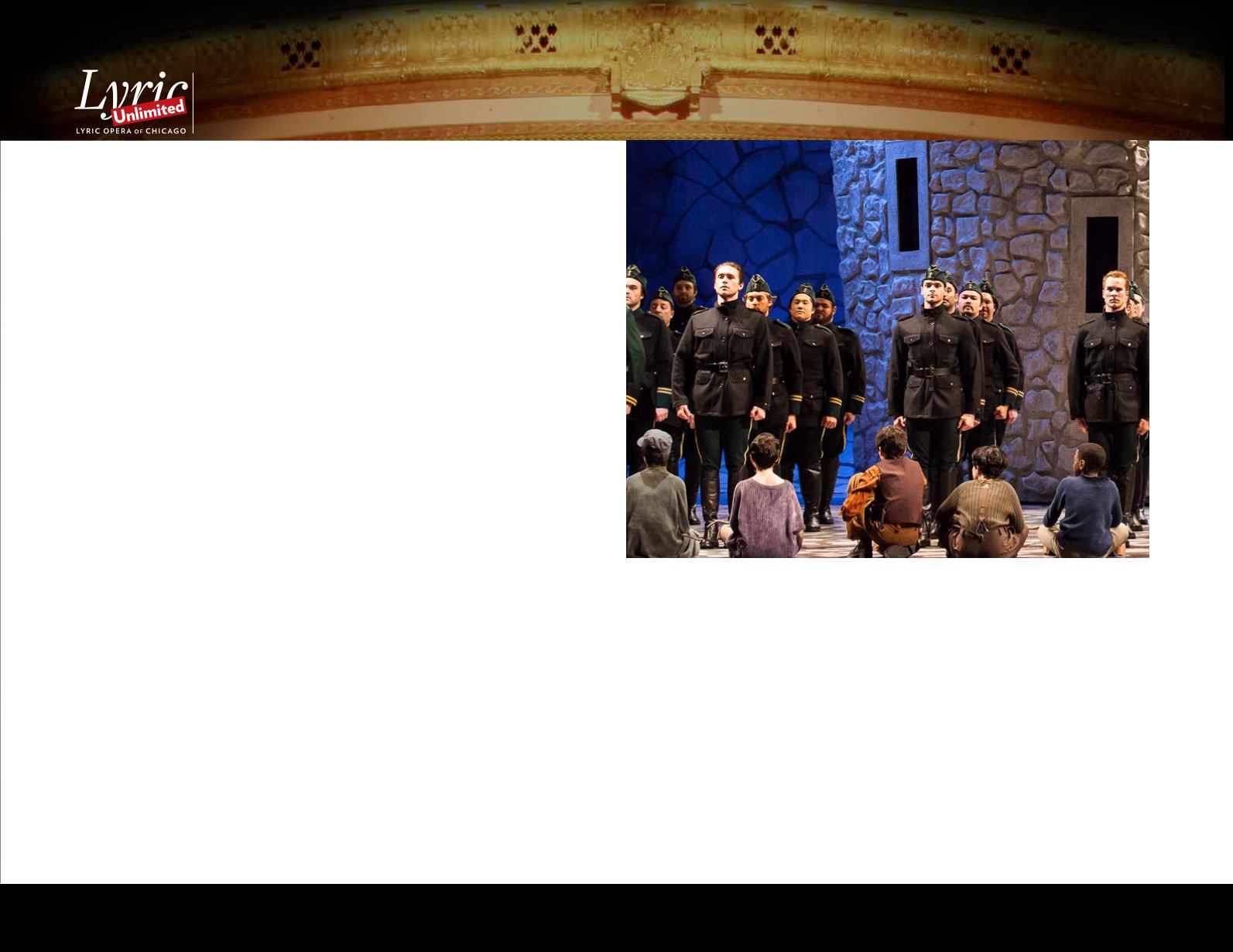

Photo: TBD

>Photo: Lynn Lane/Houston Grand Opera