O P E R A N O T E S | L Y R I C O P E R A O F C H I C A G O

32

|

November 1 - 30, 2017

cut the Volsung kids a bit of

slack. Their relationship doesn’t

have the “ick” factor of brother-

sister lovers Jamie and Cersei

Lannister in

Game of Thrones

.

Carolyn Abate and

Roger Parker, authors of the

authoritative

A History of

Opera

, suggest Siegmund

and Sieglinde “jolted Wagner

to a higher plane in his

thinking about motifs in the

dark, those intricate musical

transformations that depict

the twins’ increasing passion.”

The authors note the Volsungs’

realization that they are related

seems “to ignite them further.”

The act hits overdrive

when Siegmund pulls Wotan’s

sword Nothung out of the ash

tree and the orchestra explodes

in triumphal light with the

themes of the sword and the

Volsungs, culminating one of

Wagner’s most rapturous love

duets. Too bad

Die Walküre

doesn’t end with the happy

pair escaping into the night.

Even an illegal marriage seems

preferable for Sieglinde than

staying with that boorish bully

Hunding.

Act Two, the second

longest of the cycle (after Act

One of

Götterdämmerung

),

challenges singers and listeners.

It returns to the musical and

dramatic darkness that pervaded the

start of the opera with a different set

of relationships. Wotan and his favorite

daughter Brünnhilde, who open the act

in high spirits, will be in bitter conflict

when the curtain closes. Wotan’s ability to

control events – even in his own family – is

shattered, starting with his wife Fricka, the

goddess of the hearth and matrimony.

A strict constructionist when it comes

to matrimonial matters, Fricka demands

that Wotan disavow the immoral Volsung

union. Audiences often view Fricka as

a righteous spoilsport, but Valhalla law

is on her side. Her music ends with a

noble reference to her “rights, sublime

and glorious,” showing Fricka, too, is an

immortal, and Wotan’s equal.

As Wotan’s plans disintegrate, for the

first time in the opera we hear the music of

Alberich’s curse –

Walküre

is the only opera

in the cycle where we never physically see

the ring. The confident and sometimes

arrogant god of

Rheingold

is losing his

mojo. In front of Brünnhilde, Wotan

delivers a lengthy narration, described

by music critic Alex Ross as “the most

spectacular psychological tailspin in the

history of opera.” The quiet, contained

music accurately portrays Wotan’s utter

dejection as he realizes the fates of the ring,

the gods and, certainly, the Volsungs are

out of his hands.

For the rest of the

Ring

cycle, this is a

humbled god.

Brünnhilde, who comes

off as spirited but somewhat

one-dimensional through the

opening of Act Two, undergoes

her own transformation in

the “Todesverkündigung,”

the announcement of death

to Siegmund, who no longer

enjoys the Valkyrie’s protection.

It is a scene of majesty and

foreboding. The music starts at

a stately pace with the Valhalla

theme, but it increases in tempo

and agitation when Siegmund

tells Brünnhilde that he will not

accompany her to the joys of

the afterlife once he learns his

“sister-bride” Sieglinde will not

be at his side.

Brünnhilde, who has never

witnessed such romantic

passion and humanity, has a

profound change of heart and

agrees to fight at Siegmund’s

side, culminating a powerful

scene that, ultimately, results

in Wotan’s favorite daughter

forfeiting her rights to be a

Valkyrie. But if Brünnhilde has

lost Wotan’s support, she has

become a more sympathetic –

dare we say human – character.

Before getting into the crux

of ActThree, a quick word about

“The Ride of the Valkyries”

that opens the act, perhaps the

most famous music Wagner

ever composed. It is accessible

enough to serve as a ditty for Elmer Fudd as

he pursues Bugs Bunny, but it also possesses

the martial quality to accompany a battle

scene in Francis Ford Coppola’s

Apocalypse

Now

. As Wagner unleashes the full power

of his large orchestra, audiences can picture

winged horses soaring over mountaintops,

ridden by a very different kind of woman.

To mid-19th century sensibilities, the

presentation of women as confident and

athletic as the brash Valkyries would have

been radical. Females didn’t behave this

way. Fricka dismisses the brood as “good-

for-nothing wenches.’’ Yet the Valkyries

are the predecessors not only of a super-

hero like Wonder Woman, but the world-

class female athletes who win Olympic and

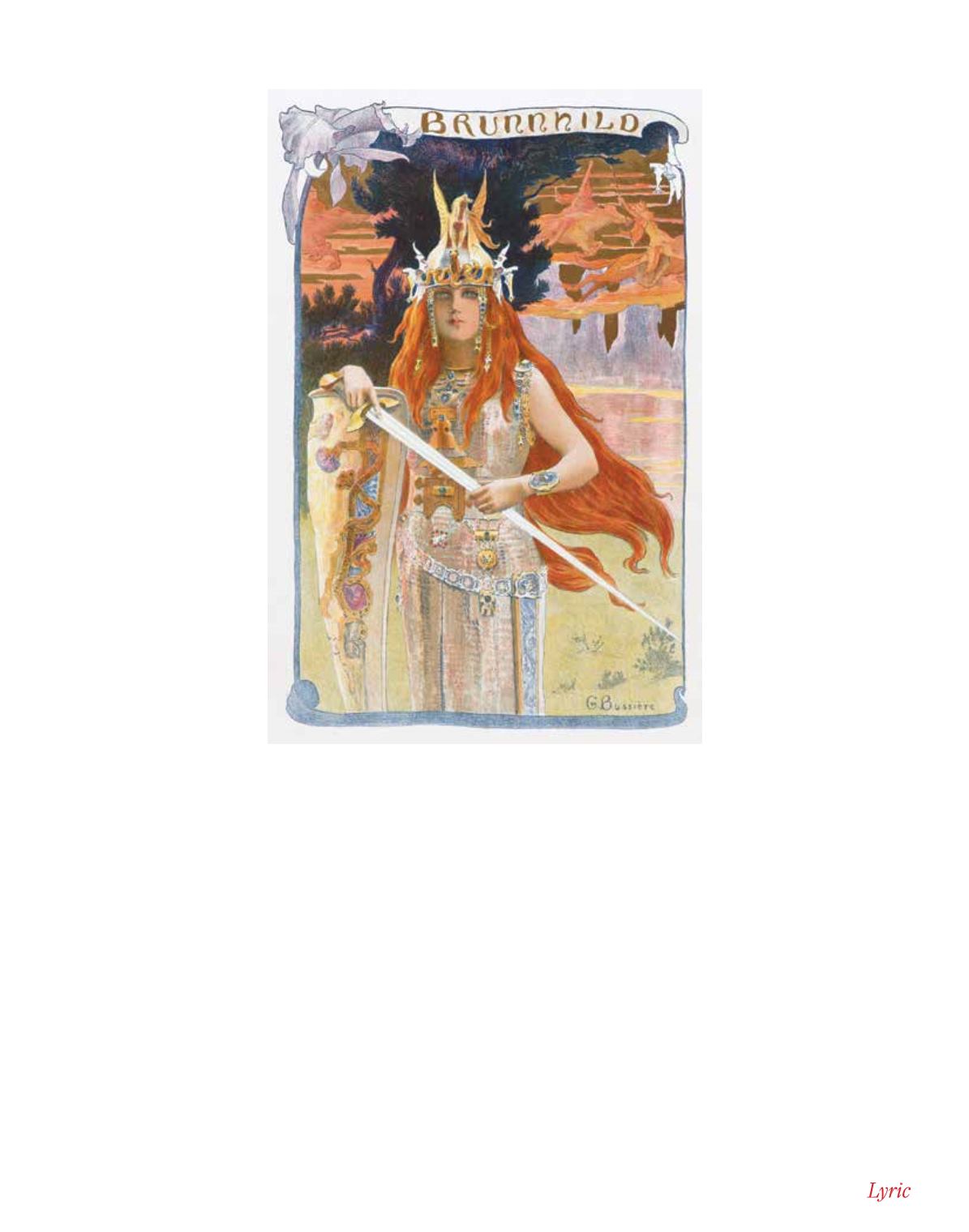

The heroine of

Die Walküre,

extravagantly depicted

by Gaston Bussiere in 1897.