34

|

November 1 - 30, 2017

Director’s Note –

Die Walküre

L Y R I C O P E R A O F C H I C A G O

The world has now moved on from

the schematic, colorful world of

Das

Rheingold

with its bold delineation of

the worlds of above, on, and under the

earth. The Gods have transformed from

a ramshackle band of Nomadic deities

into an Imperial Family suitably housed

in an awe-inspiring palace, seemingly all

powerful but at the same time hemmed in

by inherited obligations from the past and

the murky compromises of political reality.

The first two acts of

Die Walküre

therefore follow this narrowing field

of possibility by focusing down onto

intensely domestic encounters. The first

act takes place entirely in Hunding’s house

and concerns husband/wife and brother/

sister, but of course, it is still part of an

elemental epic in which a tree bearing

a magic sword grows through the walls

of the house, and Spring bursts into the

living room –- not something that happens

very often in everyday suburbia. And this

“domestic” setting also includes one of the

greatest expositions of “Anagnorisis” – the

moment of recognition in Aristotelian

tragedy – in which brother and sister,

Siegmund and Sieglinde, discover each

other’s identities. The fact that they then

consummate this recognition passionately

and sexually is Wagner’s own particular

take on the Aristotelian device.

In the second act, partly set inside the

“Imperial Palace” (Valhalla), the characters

are equally intimately connected: husband/

wife, father/daughter, brother/sister. It

is useful to remember that despite the

Ring

’s epic scale and occasional scenes of

spectacle, it is primarily a series of two-

handed confrontations. In the ultimate

operatic “domestic row” between husband

and wife (Wotan and Fricka), we learn that

the world is regulated by a strict sense of

proprieties. Wotan may rampage around

the world creating a tribe of daughters,

the Valkyries, but he cannot get away

with secretly manipulating human beings

to suit his purposes. He is fenced in by

convention and social order, which is what

gives this work its Ibsenesque quality,

highlighting the struggle of the individual

to come to terms with the obligations and

rules of society. Wagner’s Gods are very

much powerful citizens of a social and

moral world which we can all recognize,

rather than the carefree hedonists of

Olympus.

Wagner’s acute sense of human

psychology is nowhere better

demonstrated than in the relationship

between Wotan and his daughter,

Brünnhilde, and a large proportion of the

five-hour drama is given over to exploring

this. Of course she worships her father,

and cannot believe that her hero is tied

down and compromised by political and

historical reality. Like an impetuous and

idealistic teenager she takes up the cause

of rescuing Siegmund and Sieglinde,

believing that in defying her father’s orders

she is nonetheless expressing his inner

desire. This disobedience merely serves

to highlight for Wotan the miserable

compromise he has been forced to make,

and so, shamed by his daughter’s naïve

but principled idealism, he reacts with

the wounded fury of a man whose own

hypocrisy has been exposed.

The emphasis in

Walküre

on social

relationships and obligations and human

psychology suggests to us that this

drama is moving forward in time from

the world of

Das Rheingold

, bringing

us into an era in which we can all too

readily understand and identify with the

problems and conflicts that the characters

have to solve. Our relationships with

our children and our partners may not

be on such an epic scale, but they are

not materially of a different order to the

personal relationships explored here.

Walküre

moves us into the modern world,

albeit still one at a significant remove from

our contemporary experience, perhaps

abstractly located in the middle of the

last century – that is, if we need to define

an exact period. And the methodology

of our production remains the same, as

it will throughout the cycle. We set out

with our designs to create a theatrical

framework for the stage which continually

allows us to revert to its pristine, virginal

condition: the empty stage. And on that

empty stage we continually recreate the

illusion in which you will believe, even

though we will continually reveal to you,

show you, demonstrate even, how the

illusion is created. The story of this second

instalment may have become more human,

more intimate, more psychological, but it

remains a story which we will tell in the

spirit of that magical pact between narrator

and listener: “Once upon a time….”

—

David Pountney

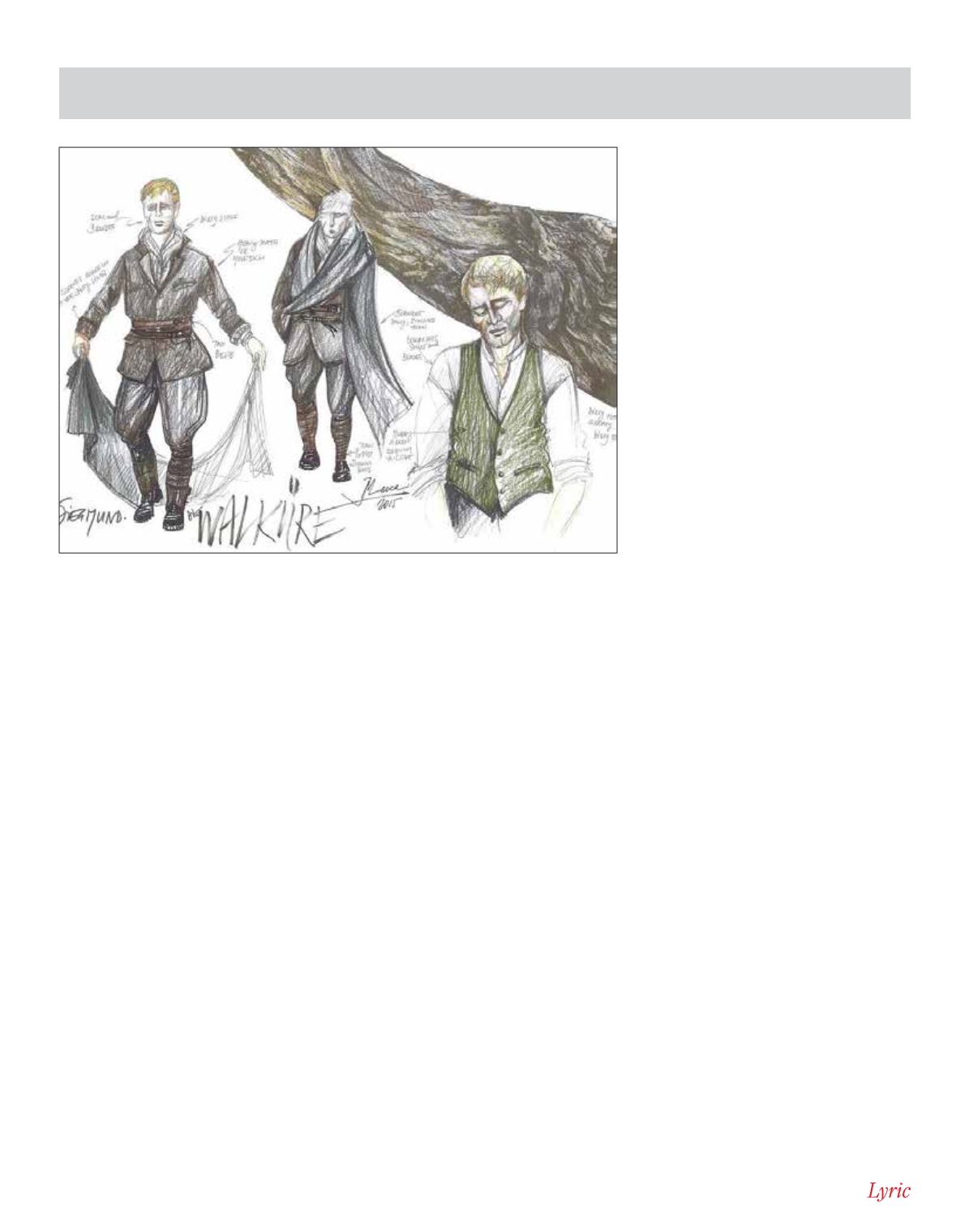

Costume designer Marie-Jeanne Lecca's costume sketch for Siegmund.