S

hakespeare’s play

Romeo and Juliet

has led a large number of

composers to base an opera on its tantalizing love story, but how

many of these operas are performed in opera houses today? You

may have heard Bellini’s

I Capuleti e i Montecchi

(

The Capulets and

the Montagues

) but who has even heard of the 1776

Romeo and Juliet

composed by Georg Benda, or the 1862 Leopold Damrosch opera of the

same name, or

Giulietta e Romeo

composed by Nicola Vaccai in 1832?

Even though

Romeo and Juliet,

the quintessential love story,

is endearing and memorable, those

qualities haven’t guaranteed that

an opera based on it will do well,

but Charles Gounod’s

Roméo et

Juliette

succeeded from the start.

Its triumphant 1867 premiere at

Paris’s Théâtre-Lyrique, and the

run of performances that followed,

was aided by a happy coincidence:

the Exposition Universelle opened

in Paris in April 1867, attracting

9.2 million visitors to the French

capital. Many visitors were looking

for entertainment; as a result,

Roméo

et Juliette

played to sold-out houses

night after night. It then traveled

to all the major opera centers in

Europe and returned to Paris as a

staple at the Opéra Comique in

1873, before finally moving to the

mighty Paris Opéra in 1888. Its

early, resounding success ensured

that it would become a part of the

international repertory — but why

did it endure when others failed?

When Gounod (1818-1893)

turned his attention to

Roméo et

Juliette

in 1867, he’d already earned

renown with an opera based on

another legendary world-famous

drama, Goethe’s

Faust

. He’d long considered setting Shakespeare’s play to

music, and was returning to a story that had captivated his attention many

years before. As a student in Rome in his mid-twenties, he began a

Romeo

e Giulietta

(probably based on the same libretto Bellini had used in 1830

for his

Capuleti

). He may have been inspired at an even earlier time, when

he was still a teenager and first heard another

Roméo et Juliette

, Berlioz’s

glorious “dramatic symphony.”

For his new opera Gounod collaborated with the same librettists,

Jules Barbier and Michel Carré, who worked with him on

Faust

. These

two tried to stay close to the language and meter of Shakespeare, using

Victor Hugo’s recently completed French translation. Barbier and Carré

selected scenes from Shakespeare’s play, but they did away with many of

the secondary characters while expanding others. They also condensed the

original play where they deemed it necessary. Although Gounod intended

to remain as faithful to Shakespeare as possible, he allowed his two

librettists to make changes to create

a text of workable length for the

opera, and to remove many scenes

that didn’t focus directly on the two

lovers. To that end, the librettists

made a bold decision in changing

the final scene; in Shakespeare, when

Juliet awakens and finds herself in

the tomb, Romeo is already dead. In

Gounod’s opera, however, Romeo

is still alive, and the lovers sing

a duet before Juliet fatally stabs

herself. The two then die together,

begging God’s forgiveness for their

unchristian suicide.

The librettists’ choice of scenes

and their rewriting can bring us

closer to understanding Gounod’s

success. It can be found in the more

concentrated way the opera tells this

iconic story. The composer was able

to create a Romantic masterpiece

of captivating melodic music,

gradually intensifying the love of

the two teenagers with exceptionally

beautiful duets in four of the five

acts. The duets highlight the lovers

while creating a magnificent and

unusual progression, linking the plot

and the music.

It’s important to remember that Gounod, a former church organist

and choirmaster, studied theology for two years before entering the

Saint-Sulpice seminary in 1846. It was only a year later that he decided

against taking holy orders and began composing operas. He wasn’t

simply a French romantic; at times he was described as very religious,

overly sensitive, hyperemotional, sensuous, and passionate. All these

characteristics he transferred to

Roméo et Juliette

. Because – like the

O P E R A N O T E S | L Y R I C O P E R A O F C H I C A G O

February 22 - March 19, 2016

|

35

Gounod’s

Roméo et Juliette

: Love Triumphs Even in Death

By Susan Halpern

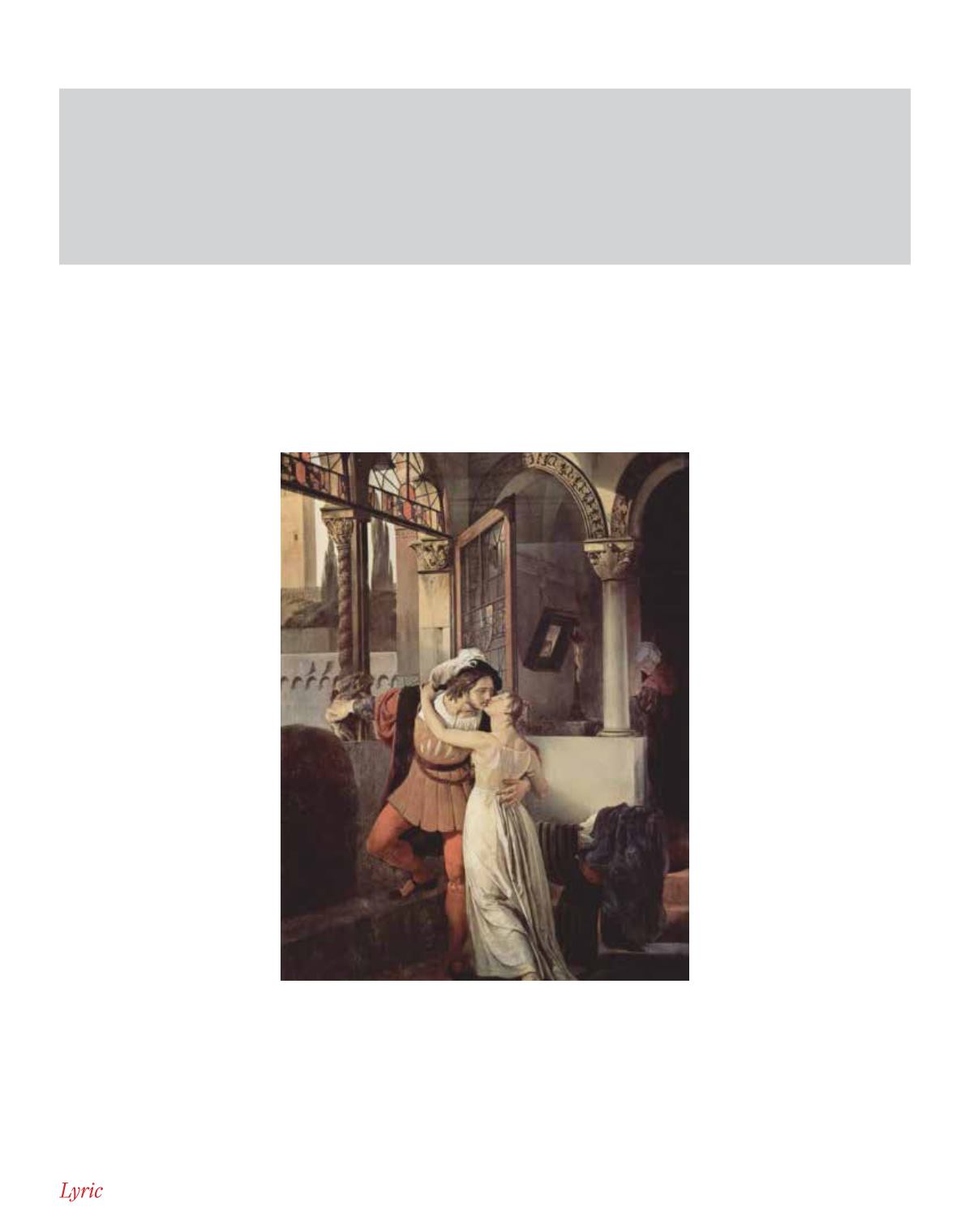

“The Last Kiss of Romeo and Juliet”

by Italian painter Francesco Hayez (1791-1882)