O P E R A N O T E S | L Y R I C O P E R A O F C H I C A G O

36

|

February 22 - March 19, 2016

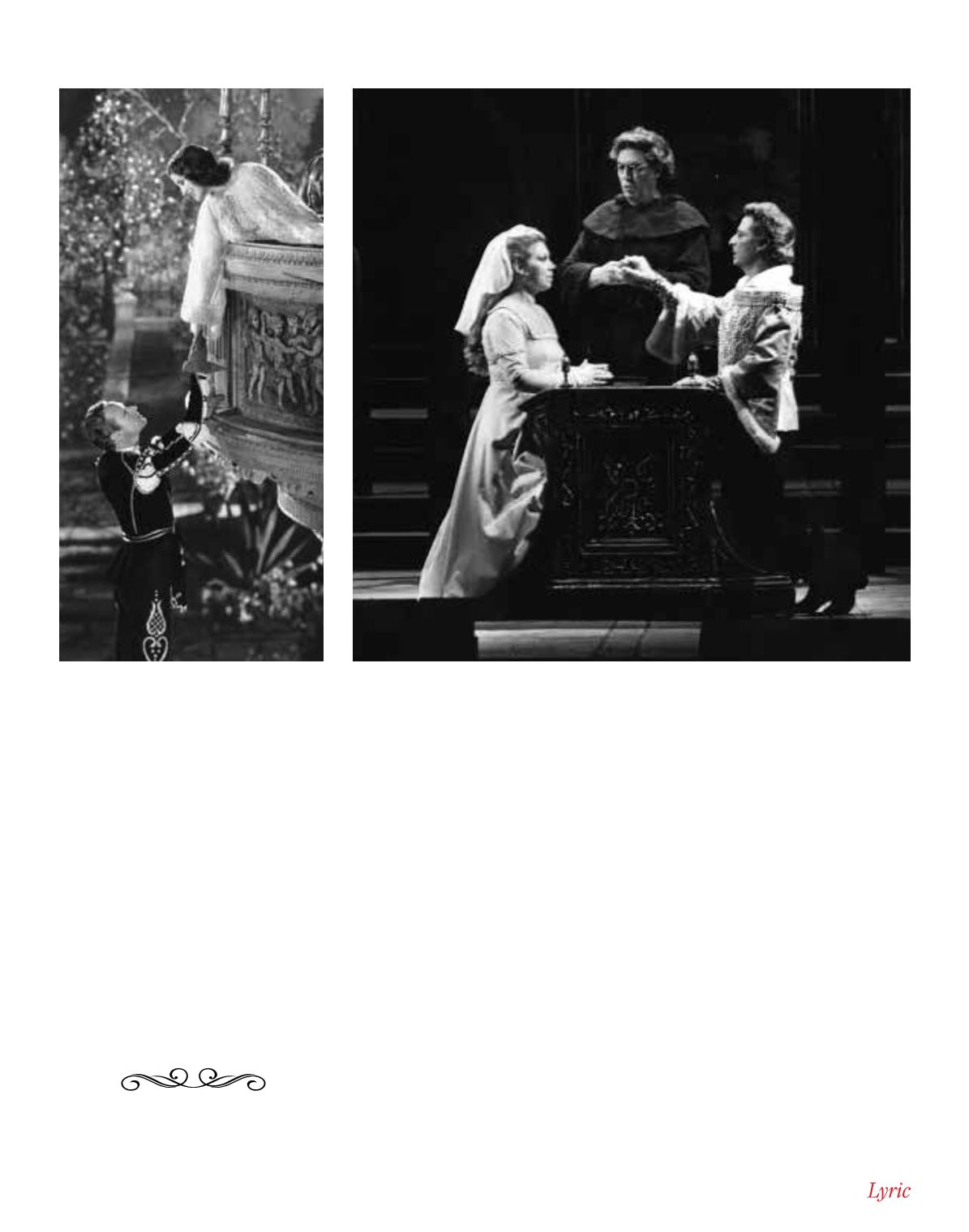

Juliet (Mirella Freni) and Romeo (Alfredo Kraus) are married by Friar Laurence (Sesto Bruscantini)

in Lyric’s 1981 production.

Leslie Howard and Norma Shearer were

Hollywood’s idea of Romeo and Juliet

in the 1930s.

great majority of his countrymen – Gounod

was a religious Catholic, it’s possible that

he included a subtle religious message in his

opera. It would have been understood in the

France of Gounod’s time that the deaths of the

lovers occurred because of their own actions,

decisions, and choices, and the lack of parental

guidance; thus many in the audience might

have interpreted this tragedy as a Christian or

Catholic cautionary tale. If we don’t interpret

the opera today as Gounod’s audience might

have done, it’s because we don’t share the

over-arching French Catholic viewpoint of

Gounod’s audiences.

In the prologue that begins

Roméo et

Juliette

, the chorus foreshadows the action to

come as it introduces the feud between the

two families, the Montagues and the Capulets.

We soon sense its edge of violence, as well as

the love between Romeo and Juliet. In the

mazurka opening Act One, Gounod’s music

highlights the stark contrast between inner

emotional feelings and the sounds of the

festivities. The dance music, which returns

after Juliet appears for the first time, and again

at the end of the act, provides the atmosphere

for the whole act and creates its unity, while

helping to establish the act’s pageantry.

Although both Shakespeare’s play and

Gounod’s opera are divided into five acts,

the Barbier-Carré libretto doesn’t follow

Shakespeare’s sequence of scenes. Instead, it

extracts and condenses the best-known and most

“operatic” scenes and then links them together:

the Capulets’ masked ball, the scene in Juliet’s

garden, the hot-blooded duels in the street, the

scene in Friar Laurence’s cell, Juliet’s soliloquy

before taking the potion, and the tomb scene.

Gounod was pleased with how he conceived

the work’s structure, and wrote expressing his

satisfaction while he was still working on it: “The

ending of the first act is brilliant, of the second

tender and dreamy, of the third animated and

grand with the duels and the exile of Romeo, of

the fourth dramatic and of the fifth tragic. It is a

beautiful progression.”

In his writing, however, Gounod had

to conform to the demands of Parisian opera

audience. They required not only that there

be five acts and a strong element of spectacle,

but also that each opera have a ballet as well as

voices of a predictable number and type -- two

prominent sopranos, as well as a tenor and a

baritone. To satisfy this requirement Gounod

created a second soprano: the “pants” role of

Stephano, Romeo’s page, who doesn’t appear

in the original Shakespeare play.

TONY ROMANO