9

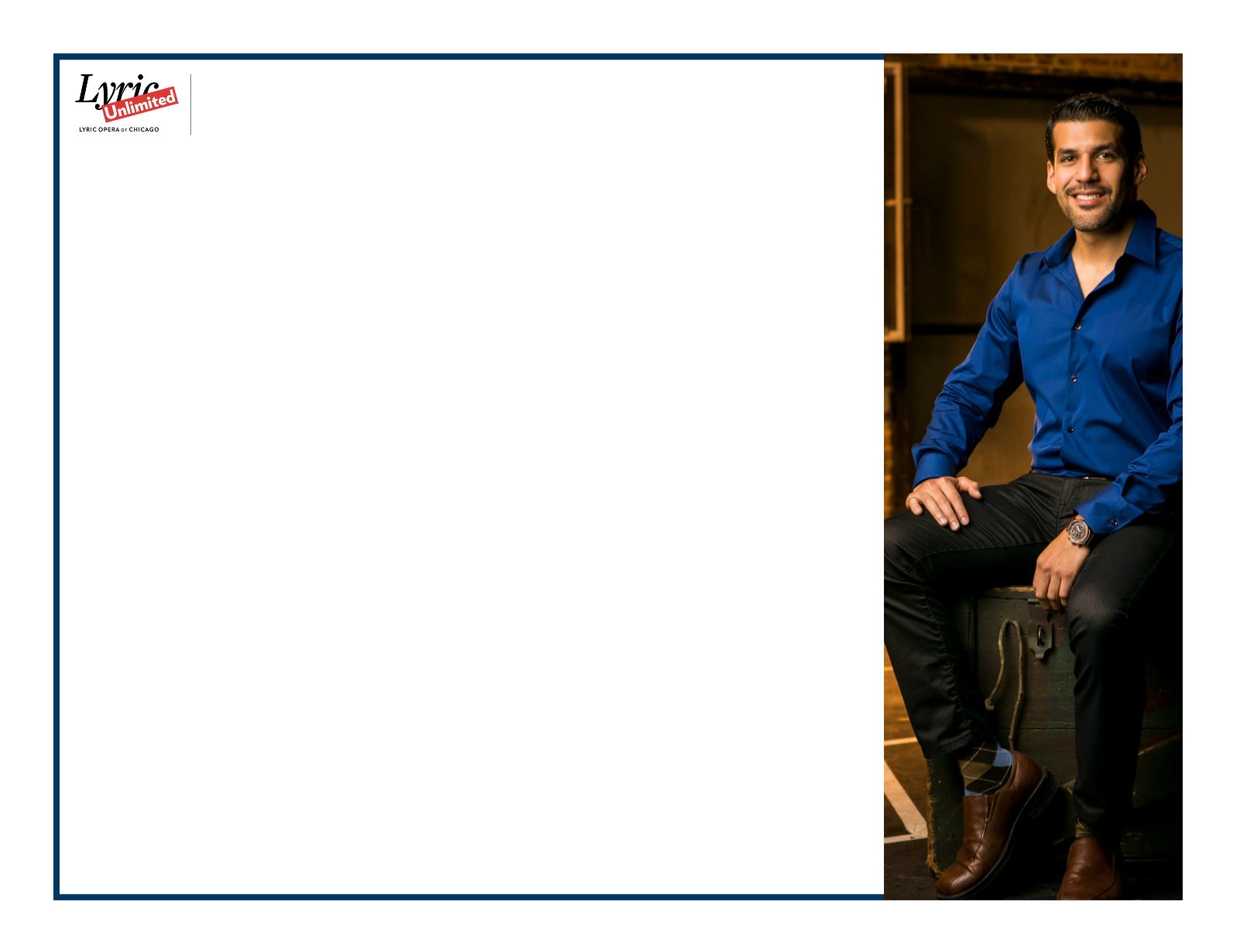

An Exchange with

Jimmy López

During the summer of 2015, writer Maia

Morgan and Lyric audience education

manager Jesse Gram sent

Bel Canto

composer Jimmy López a series of

questions. Here are the results.

MM:

What music did you hear growing up? What were

your early experiences with music? What are your

biggest musical, cultural, or literary influences as a

composer?

JL:

One could say that, in my case, there’s before Bach

and after Bach. My first encounter with Bach’s music

was in 1991, when I listened to a music teacher playing

his two-part invention No. 13 in A minor at my school.

Until then I was only listening to regular mainstream pop

music, but after that I started listening almost exclusively

to classical music. I started playing the piano when I

was five but I was not really serious about it; my sister

was taking lessons and I liked it so I decided to do it as

well, but it was only after my encounter with Bach that I

started to consider dedicating my life to music.

I’ve had several influences at different stages of my

career. After Bach, from whom I learned polyphony,

I started to discover Mozart’s melodic genius. I then

went on to admire Beethoven’s motivic discipline, and

in my late teens, I discovered Stravinsky’s revolutionary

rhythmical structures. His orchestral music in particular

struck a chord with me because, at about the same

time I discovered his music, the Lima Philharmonic

Orchestra (which used to rehearse at my high school’s

auditorium) was founded. You can imagine what a

luxury it was for a young, aspiring composer to be able

to listen to three-hour-long orchestra rehearsals almost

every single night.

Also around that time, I cemented my knowledge of

harmony with Peruvian composer Enrique Iturriaga,

who taught me all about it using Schoenberg’s

Harmonielehre

. Later on, when I moved to Finland, I

studied Debussy’s refined orchestrations and Sibelius’s

architectural formal thinking. In my early and mid-

twenties I was truly fascinated by Gérard Grisey’s

monumental

Les Espaces Acoustiques

and with

Krzysztof Penderecki’s early period. The list goes on, with

composers such as John Adams, Georg Friedrich Haas,

John Corigliano, Magnus Lindberg, Anders Hillborg, and

several others making a deep impression on me.

JG:

Are there other opera composers who’ve inspired

you?

JL:

It’s interesting how we tend to categorize composers

as “opera composers,” “film composers,” “concert

music composers,” etc. Even though those categories

make total sense, I don’t listen to music that way. It

is true that certain composers specialize in a specific

genre and are invariably associated with it, such as

Rossini (opera), Chopin (piano), and Herrmann (film),

but I tend to prefer composers who have transcended

those labels, like Mozart, Beethoven, Debussy, or

Stravinsky. They wrote in practically every genre

available to them and were mostly successful at it, so

I’d like to follow their steps. But let me explain what I

mean when I say that I don’t listen to music that way.

A composer like Wagner can be justly categorized as

an opera composer, but within his operas there is so

much great symphonic music that when I listen to him,

I just hear great music, regardless of whether there are

words involved or not. Sibelius never wrote an opera

and he is mostly known for his symphonies, but he

Photo: Todd Rosenberg