14

The Troubled History behind

Bel Canto

Although both the novel and the opera are works of

fiction,

composer Jimmy López, a native of Peru, felt it was important for

the opera to allude to some of the actual events that inspired

Bel Canto

.

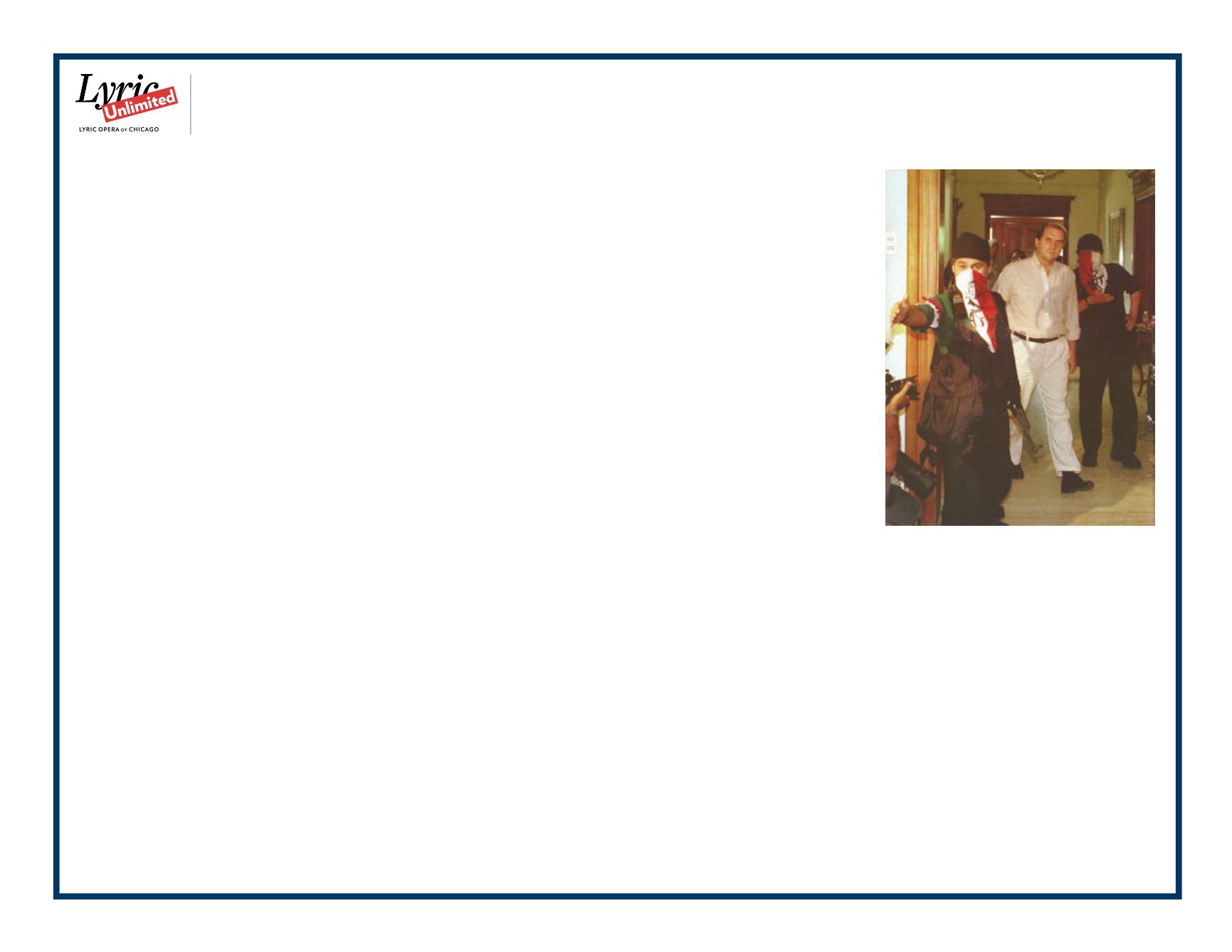

On December 17, 1996, the home of Japanese ambassador Morihisha Aoki in

Lima, Peru, overflowed with illustrious guests—government ministers, Supreme

Court justices, and Peruvian president Alberto Fujimori’s mother, sister, and

brother. They were assembled to celebrate the 63

rd

birthday of Emperor

Akihito. In the midst of the festivities, fourteen masked members of Marxist

rebel group MRTA blasted a hole in the garden wall and took everyone

present hostage. “This is the Túpac Amaru Revolutionary Movement,” a voice

announced. “Obey and nothing will happen to you.”

Ambassador Aoki pleaded with the guerrillas to free his guests. “I, alone,” he

said, “am important enough for you to bargain with.” But although the rebels

would release many hostages in the weeks to come, for 72 people it was the

start of an ordeal that would last four months. The rebels demanded, among

other things, the release of several hundred of their MRTA comrades from

prison, including rebel leader Nèstor Cerpa’s wife. Cerpa said they would

start killing captives if President Fujimori did not appear for face-to-face talks.

But when their deadline came and went, Cerpa backed down. “We’re not

killers,” he told one of the hostages.

Fujimori did assemble a negotiation team, which included the Peruvian

archbishop and Red Cross, as well as the Canadian ambassador, Anthony

Vincent, who had briefly been a hostage himself. Nevertheless, the

government repeatedly rejected the militants’ demand to release imprisoned

MRTA members and secretly laid plans to storm the residence.

As portrayed in

Bel Canto

, most of the rebels occupying the residence were

young and unseasoned—many only in their teens. As the weeks dragged

on, one of the hostages remembers seeing one of the teenage soldiers

crying. When he asked her what was wrong, she said she was homesick.

Other hostages requested a guitar for some of the rebels who wanted to

learn how to play; it was brought in by the Red Cross. Later, a Peruvian

newspaper would report that a microphone placed inside the instrument

had helped government officials

monitor the rebels’ activities inside

the mansion. Former hostage

Rodolfo Munante Sanguinetti,

Peru’s minister of agriculture,

said that while in captivity he’d

spoken often to the rebels about

government projects he’d worked

to accomplish in the country’s

impoverished farming regions. At

one point he observed that one of

the rebels liked to draw. Munante

offered advice to the teen on his

artwork. Also, as in the opera, the

rebels did play soccer in the house

and were doing so when the raid

began.

On April 22, 1997, four months

into the siege, military commandos

raided the residence. In the event of a government attack, the rebels had

orders to kill their captives immediately. Munante remembers lying on the

floor, plaster raining down from explosives detonated by the military and the

young man he’d helped with his drawing aiming his gun at him. “He was

going to shoot me,” said Munante. “But he didn’t.” The rebel lowered his gun

and left the room. He and the rest of the MRTA rebels were killed. One of the

hostages and two commandos also lost their lives.

Photographs of the president walking among the headless bodies of the rebels

were broadcast on television. Following the mission, Fujimori’s popularity ratings

doubled to nearly 70 percent. But rumors began to circulate that surrendered

MRTA members had been summarily executed. According to a Defense

Intelligence Agency report, Fujimori had ordered the commandos to “take

no MRTA alive.” Twelve years later, in 2009, Fujimori was convicted of murder,

aggravated kidnapping, and battery, as well as crimes against humanity for

human rights violations committed during his time in office.

MRTA guerrillas in the Japanese Embassy, Lima,

Peru, 1996.