O P E R A N O T E S | L Y R I C O P E R A O F C H I C A G O

February 8 - March 13, 2016

|

29

Born for One Another: How Strauss and Hofmannsthal

Brought

Der Rosenkavalier

to Life

By Mandy Hildebrandt

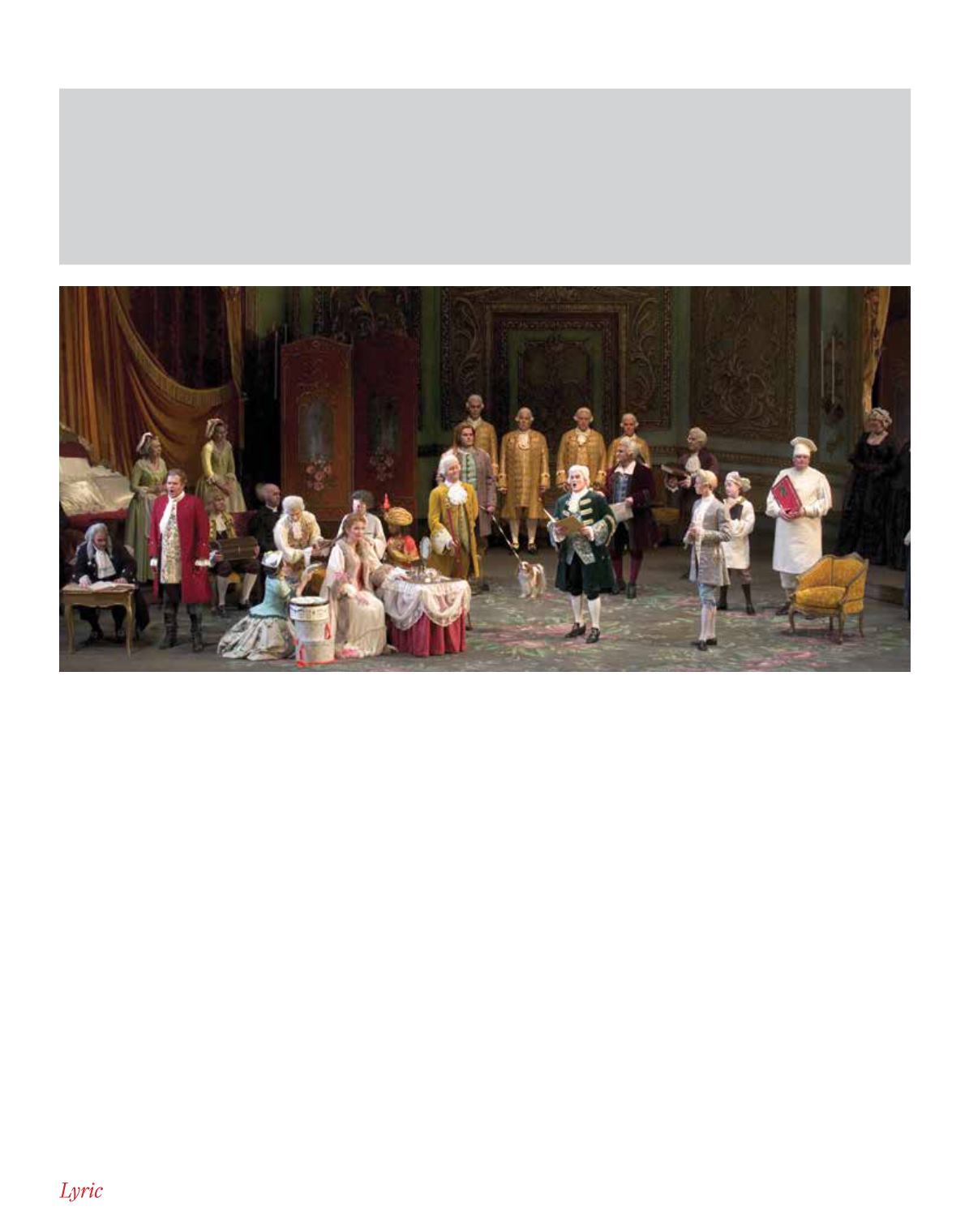

A singer (Bruce Sledge) performs for the Marschallin (Anne Schwanewilms) during her morning levée:

Act One of

Der Rosenkavalier

at Lyric, 2005-06 season.

ROBERT KUSEL

It would be difficult to find two men more

different in personality and artistic views than

Richard Strauss and Hugo von Hofmannsthal,

and probably few would have bet money on

their partnership’s success. The former was

a demanding and sometimes petty Munich

native, the latter an ultra-sensitive and tem-

peramental Viennese. The two never shared a

social friendship but, surprisingly, they made

their professional relationship work. In fact,

they became one of the most celebrated operat-

ic composer-librettist teams since Mozart and

Da Ponte. This success proved true the predic-

tion of Strauss, who’d written to Hofmannst-

hal in 1906, “We were born for one another

and are certain to do fine things together.”

Their partnership lasted 23 years and produced

six operas, of which

Der Rosenkavalier

– an

astonishing examination of feminine psychol-

ogy in a bittersweet comedy, set to a ravishing

score – is unquestionably the most popular.

In early 1909 they’d just completed

Ele-

ktra

when Hofmannsthal approached his col-

league with a new scenario. What would

ultimately become

Der Rosenkavalier

started

as a romantic-burlesque plot set in 18th-

century Vienna, with dashing Octavian out-

witting lecherous Baron Ochs for the hand of

young Sophie. At that point the figure of the

Marschallin was still a mere shadow, but her

importance would increase beyond all recogni-

tion as the opera progressed.

One of Hofmannsthal’s inspirations was

Mozart’s

The Marriage of Figaro

, and there

certainly are some parallels between the two

operas: in each, three principal roles (one of

them a trouser role) are sung by sopranos,

and the principal male singers are baritones or

basses, with various tenors relegated to subsid-

iary comic parts. As with Mozart’s Cherubino,

there’s an extra plot twist that finds Octavian

impersonating a girl: thus, a soprano portrays

a man pretending to be a woman!

As soon as he’d received Act One from

Hofmannsthal, Strauss began working on the

score with huge enthusiasm. (Years afterward,

he commented that the wonderful text practi-

cally set itself to music!) Hofmannsthal’s Act

Three took many months to complete; he

wanted to do the opera full justice, and insisted

on waiting for the right mood to come over

him before creating a certain scene. Strauss

understood this completely and didn’t mind

waiting more than a year before diving into

Act Three.

Despite this delay, the act that gave them

the most problems was actually the second. In

July 1909 Strauss wrote Hofmannsthal a long

letter with detailed criticisms. He emphasized

that Act Two lacked the “necessary clash

and climax,” and that the audience should

“laugh, not just smile or grin!” Fortunately,

Hofmannsthal was in no way offended; he

respected and admired Strauss’s shrewd sense

of theater, and willingly reworked the act.

Nearly all the final action of Act Two follow-

ing Baron Ochs’s entrance came out of the

composer’s suggestions (including such vital

details as Ochs’s neglecting to tip Annina,