O P E R A N O T E S | L Y R I C O P E R A O F C H I C A G O

30

|

February 8 - March 13, 2016

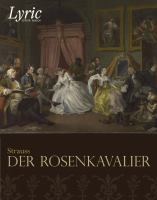

A climactic scene from director Robert Wiene’s famous silent film (1926) based on

Der Rosenkavalier

. Pictured left to right are Paul Hartmann as the

Field Marshall (a character not included in the opera), Huguette Duflos as the Marschallin, Elly Felicie Berger as Sophie, and Jaque Catelain as Octavian.

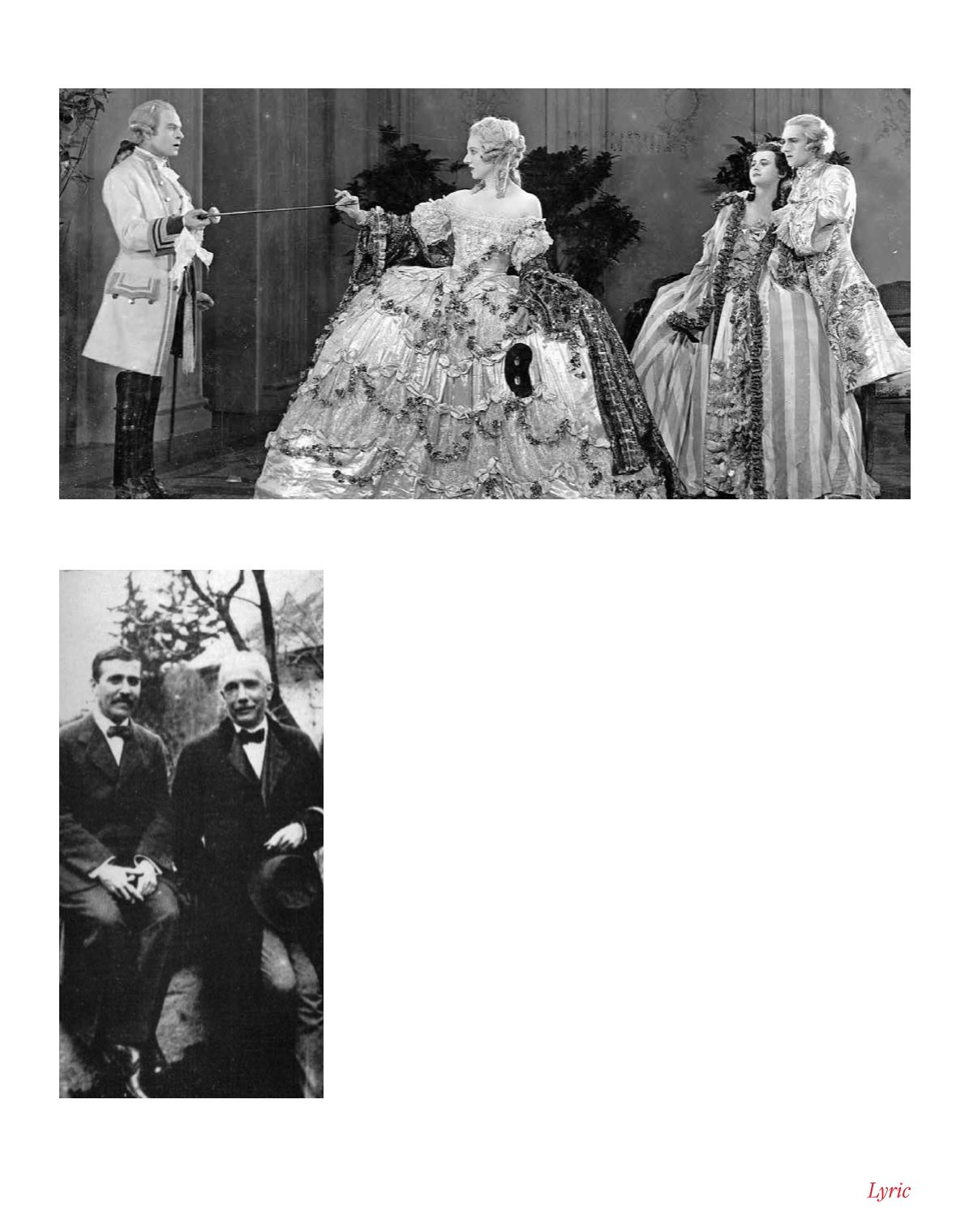

One of few surviving photos of

Hofmannsthal (left) and Strauss.

thus motivating the Italian intriguers’ change

of allegiance to Octavian). But contrary to the

usual assumption, the famous waltz conclud-

ing Act Two wasn’t Strauss’s idea at all: “Try

and think of an old-fashioned Viennese waltz,”

Hofmannsthal wrote to the composer in April

1909, “sweet and yet saucy.”

For years audiences have assumed that it

was a standard Viennese custom to present a

silver rose to a future bride, so it’s surprising

to learn that this was another Hofmannsthal

invention. The opera’s title,

Der Rosenkavalier

(“The Cavalier of the Rose”), chosen quite

late, was actually a suggestion from Pauline

de Ahna, Strauss’s wife and formerly a dis-

tinguished soprano. Until six months before

the premiere, Strauss and Hofmannsthal had

planned to title their opera

Ochs auf Lerchenau

(lit. “ox in the lark-meadow”), highlighting the

Baron and his comedic moniker.

Strauss once described the self-satisfied

Baron as “a rustic Don Juan beau of about

thirty-five, always a nobleman (even if a rather

boorish one) … a bounder

inwardly

; but on

the surface sufficiently presentable…” It’s clear

from the start that Ochs lacks money, and that

it’s his prospective father-in-law’s wealth that

accounts for his proposing marriage to Sophie.

We see, too, that he doesn’t mind pursuing the

Marschallin’s maid Mariandel (the disguised

Octavian) while boasting of his wedding plans.

Ochs’s comedy originates not only in his

attempted womanizing, but especially in his

absolute obsession with his own title, some-

thing not uncommon in old Vienna – and

actually still prevalent there! Ochs is so full

of himself that he considers his proposal an

incredible blessing for Sophie (her

nouveau

riche

father, Faninal, is, of course, ecstatic

at the prospect of his daughter becoming a

Baroness). The Baron is easily the opera’s

most amusing character, but Strauss and Hof-

mannsthal did this rowdy figure honor with

an unexpected moment of dignified discretion:

in Act Three, when he finally understands the

Marschallin’s actual relationship to Octavian,

he proves himself a man of the world and

agrees to remain silent about it.

With the opera completed and the Dres-

den premiere fast approaching, Strauss and

Hofmannsthal were increasingly preoccu-

pied with finding the ideal Ochs. For all the

major roles, they knew the acting abilities of

“ordinary operatic singers” just wouldn’t do,

and Ochs required an especially gifted actor.

When bass-baritone Karl Perron was assigned

the part, Hofmannsthal’s disappointment was

particularly acute; not because he didn’t admire

Perron as an artist (he’d previously created two

powerfully dramatic roles for Strauss, Jocha-

naan in

Salome

and Orest in

Elektra

), but he

believed Perron lacked the necessary comedic