O P E R A N O T E S | L Y R I C O P E R A O F C H I C A G O

February 8 - March 13, 2016

|

31

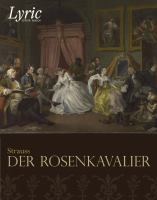

The first Octavian, Eva von der Osten, and the first Marschallin, Margarethe Siems, with costume sketches for their characters

by Alfred Roller for the 1911 Dresden world premiere.

flair. Refusing to accept a merely adequate

Ochs, Strauss and Hofmannsthal considered

cancelling the premiere if Perron didn’t live up

to expectations. Hofmannsthal was also wor-

ried about the casting of Octavian, since many

possible artists were physically wrong for the

role: “Oh well, if all buffo basses are long and

lean and only the Quinquins [Octavian’s nick-

name] thick and fat, I may as well close down!”

Strauss himself was displeased about the

cuts forced on him by Dresden’s general direc-

tor – for example in Ochs’s long speech in Act

One, which wouldn’t raise an eyebrow today

but was considered too lewd in 1911. For the

same reason, Octavian and the Marschallin

weren’t allowed to be seen in bed together un-

til a couple of decades into the opera’s perfor-

mance history.

Despite all the difficulties, the premiere

on January 26 was a brilliant success. The

Marschallin was created – surprisingly, but

very successfully – by a star coloratura sopra-

no, Margarethe Siems. Perron sang Ochs, and

Octavian was portrayed by a Wagner soprano,

Eva von der Osten, who happened to look

great in trousers. Sophie was Minnie Nast, the

Dresden company’s longtime resident ingénue.

In the following months and years, the opera

experienced a continuous and overwhelming

triumph, ensuring its place in the repertory to

this day.

In contrast to the originally planned

burlesque opera,

Der Rosenkavalier

in its final

form, although cheerful, is profoundly psycho-

logical, for which we can thank the Marschal-

lin. (It’s important to remember that Strauss

and Hofmannsthal never visualized her as a

motherly figure but as an attractive woman in

her early thirties, who, when in a morose frame

of mind, sometimes

feels

like an old lady.)

It’s the Marschallin’s depth of personal-

ity and worldly wisdom that make her so

appealing. Instead of being only an unsatis-

fied woman cheating on her absent husband,

we witness her sadly reflecting on the world’s

changes and her longing for time to stand still.

She has deep feelings for Octavian, but she

realizes that their age difference must soon end

the affair. Her sad gentleness, combined with

the inner strength and dignity with which she

acts throughout the opera, can’t fail to make

the audience feel for her.

Octavian is less complex: just 17 years

old, inexperienced, sometimes possessive, and

rather short-tempered. His feelings towards

the Marschallin have all the passion of a first

love, but it’s not necessarily

true

love. If it

were, how could he transfer his affections

so easily from one woman to the next? One

glance at Sophie and he’s instantly in love with

her! Octavian isn’t mature enough to under-

stand the Marschallin’s emotions and motives.

When she predicts that he’ll soon leave her for

a younger woman, his teenage mind promptly

jumps to the conclusion that she doesn’t love

him as much as he loves her.

Octavian’s first meeting with Sophie con-

veniently occurs shortly after his quarrel with

the Marschallin (in Hofmannsthal’s words,

“Quinquin falls for the very first little girl to

turn up”). Sophie can’t match the Marschal-

lin as a dominant female figure; the librettist

described her as “a very ordinary girl like doz-

ens of others.” But to do her justice, Sophie

definitely has guts. She may be dependent on

Octavian’s help to free herself of Ochs, but

she asks him for it instead of simply bowing to

the situation. Later, in Act Three, she has the

confidence to plant herself in front of Ochs and

warn him never to come near their house again.

When the Marschallin, Octavian, and

Sophie finally come together for the first time,

it’s up to the Marschallin to bring order into

the confusion. She handles herself – and every-

one else – with gracious authority. Octavian is

caught between two women whose differences

now become very obvious: the Marschallin

preserves her controlled dignity and gently

questions Sophie, who promptly turns into

a nervous chatterbox. Following the last cli-

mactic phrases of the soaring final trio, the

Marschallin’s last line, “In Gottes Namen” –

“In God’s name” – suggests both her sacrifice

and her blessing.

Why does the Marschallin renounce Octa-

vian so easily? Does she know she’s already lost