O P E R A N O T E S | L Y R I C O P E R A O F C H I C A G O

November 19 - December 7, 2016

|

29

B

y 1908, Jules Massenet had settled

comfortably into his role as French

opera’s elder statesman. The 66-year-

old composer divided his time between his

Parisian apartment on Rue de Vaugirard, his

country house at Égreville, and Monaco, where

he was a regular guest at the royal palace. He’d

long since given up his teaching duties at the

Conservatoire, but continued writing new

operas at a rate of about one every two years.

Although critics and younger composers had

started to consider his style outmoded, his new

works still enjoyed popular success.

Massenet’s fortunes, however, were about

to change. An attack of rheumatic pains,

which would confine him to bed for much of

the coming year, was followed in May 1909

by something far more devastating: his opera

Bacchus

was an unmitigated disaster. The

experience, although not wholly unforeseen,

came as a shock to a composer whose technical

abilities and theatrical instincts had allowed

him to side-step failure for much of his career.

Discouraged and bedridden, Massenet found

solace only in his work. From his labors

emerged

Don Quichotte

, the elegant heroic

comedy that would stand as his final triumph.

For most of his life, Massenet had

enjoyed success. He won the prestigious Prix

de Rome at just 21 and was appointed to

a professorship at the Paris Conservatoire

while still in his thirties. In the aftermath of

the Franco-Prussian War, when the grand

operas of Meyerbeer – which had dominated

Parisian stages for the previous half-century

– were falling out of fashion, Massenet rose

to prominence as a musical dramatist who

could situate large-scale emotions within more

natural and more intimate settings. Although

his earliest foray into opera – the now-forgotten

La grand’tante

from 1867 – prompted one

critic to suggest that Massenet should stick to

orchestral writing, the moderate success of

Le

roi de Lahore

in 1878 was followed in 1884

by

Manon

, the work that would establish his

international reputation.

In the decade that followed, Massenet

could do no wrong.

Werther

quickly became

a fixture of opera houses worldwide, and

Thaïs

, although not as well-known today,

was even more popular during Massenet’s

lifetime. Even in the first years of the 20th

century, new Massenet works could still fill

theaters. His most notable late-period success,

Ariane

(1906), a retelling of the Greek myth

of Ariadne and Bacchus, did well enough that

Massenet’s publisher, Henri Heugel, decided

there should be a sequel.

Yet everything about

Bacchus

seemed

doomed from the start. The fact that the

heroine had died at the end of

Ariane

was

of little concern to librettist Catulle Mendès,

who not only devised an implausible way of

bringing her back to life, but also transplanted

the lovers into the world of the

Ramayana

, a

Sanskrit epic! The normally cordial Massenet

privately despised

Bacchus

’s libretto. When

the dead body of Mendès was discovered in

a railway tunnel one morning in February

1909, only three months before the premiere,

Massenet pleaded with his publisher to have

the opera scrapped. Heugel refused.

Bacchus

opened three months later and was withdrawn

after only six performances. Today it remains

the only Massenet opera that has never been

revived or recorded.

Massenet had started sketching the music

for

Don Quichotte

earlier that year, but after

the debacle of

Bacchus

he took to it with

renewed vigor. Yet for a composer so recently

stung by failure, the story of Don Quixote was

an odd choice. In the three centuries since the

first appearance of Cervantes’s novel (the first

part was published in 1605, the second in

1615), the knight of La Mancha had become

one of the most recognized figures in western

literature, and numerous poets and dramatists

had reused the novel’s characters and stories

for their own artistic ends. Yet while

Don

Quixote

continued to grow in stature, most

of the works it inspired fell quickly into

obscurity.

Like Ludovico Ariosto’s epic poem

Orlando Furioso

, published a century earlier,

Don Quixote

was mined extensively for opera

plots during the 17th and 18th centuries: in

addition to the knight’s own adventures, the

story of a young couple, Cardenio and Lucinda

(from the first book) and the wedding of the

wealthy Camacho (from the second) were

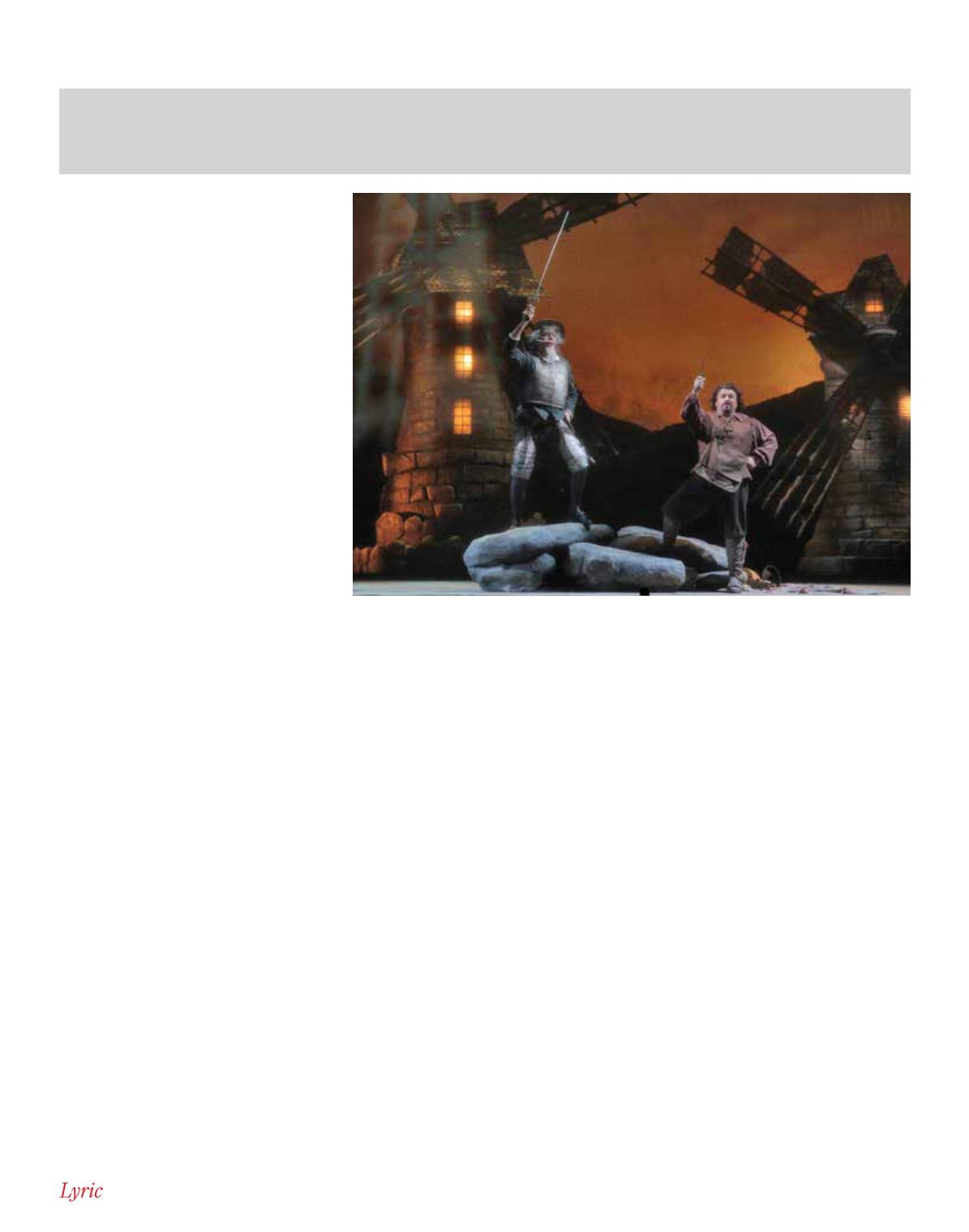

Ferruccio Furlanetto (Don Quichotte) and Eduardo Chama (Sancho) at San Diego Opera, 2014.

KEN HOWARD/SAN DIEGO OPERA

A Final Triumph: Massenet’s

Don Quichotte

By Jesse Simon