O P E R A N O T E S | L Y R I C O P E R A O F C H I C A G O

30

|

November 19 - December 7, 2016

especially popular. Indeed, between 1680 –

when the now-lost

Il don Chisciot della Mancia

by Carlo Fedeli received its first performance

in Venice – and the beginning of the 20th

century, more than 60 different operas inspired

by

Don Quixote

were performed in Europe.

Dozens of composers, including

Telemann, Salieri, and Paisiello, tried their

hand at operas based on

Don Quixote

, but none

of their efforts enjoyed any degree of long-

term popularity. In Massenet’s own time, the

Austrian composer Wilhelm Kienzl created an

adaptation of

Don Quixote

(1898) so disastrous

that he would not compose another opera for

13 years. The large number of forgotten stage

works that have accumulated in the centuries

since Cervantes’s death might suggest that the

true genius of

Don Quixote

lies in its resistance

to adaptation.

The prospect of obscurity didn’t deter

Jacques Le Lorrain, who may have recognized

something of himself in the gaunt, dream-

bound figure of Don Quixote. The son of

a shoemaker, Le Lorrain learned the family

trade in his youth, but moved to Paris in

1881, seduced by dreams of the literary life.

Despite publishing several volumes of poetry,

he struggled to make a living as a writer and,

in 1896, opened a shoe repair shop; in his

spare time he worked on

Le Chevalier de la

longue figure

, a verse drama based loosely on

Cervantes. Respiratory problems eventually

forced him to leave Paris for the healthier air

of the south, but he returned to the capital

ILLUSTRATIONS COURTESY OF CUSHING MEMORIAL LIBRARY & ARCHIVES, TEXAS A&M UNIVERSITY

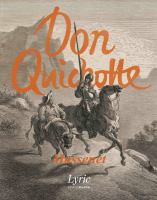

Jules Massenet and the legendary bass who created

Don Quichotte

in 1910, Feodor Chaliapin.

after receiving word that his play was to be

performed. On April 3, 1904, he was carried

to the premiere at the Théâtre de Victor Hugo

on a stretcher. Two days later, he died.

Le Lorrain’s play was no adaptation:

although he retained the famous windmill

episode and makes passing reference to other

events from the novel, the characters are

notably different, and the story of a pearl

necklace stolen from Dulcinée by a group

of bandits seems to have sprung from Le

Lorrain’s imagination. Despite a generally

warm reception from the public, both the

play and its author seemed destined to follow

the countless other stage versions of

Don

Quixote

into obscurity. Had it not been for

Raoul Gunsbourg, who saw the play during its

initial run, Le Lorrain’s name might have been

forgotten completely.

Gunsbourg, the charismatic director of

the Opéra de Monte Carlo and a friend of

Massenet, had been searching for a vehicle

for the internationally celebrated Russian bass

Feodor Chaliapin and immediately saw the

potential in Le Lorrain’s drama. He gave

the play to librettist Henri Cain, who had

collaborated with Massenet most recently on

the Beaumarchais-inspired

Chérubin

(1905).

Massenet himself didn’t seem to mind that

the story diverged so greatly from Cervantes.

Indeed, he was especially taken with Le

Lorrain’s decision to replace the novel’s

Aldonza – the woman Quixote idealizes as

“Dulcinea” – with the beautiful, inwardly

melancholic Dulcinée. No doubt he found

the latter more suited to Lucy Arbell, the

vocally and dramatically captivating Parisian

mezzo-soprano (

née

Georgette Gall) who had

spent the past five years acting as Massenet’s

unofficial muse.

Chaliapin, for whom Massenet created

the title role, was especially enthusiastic. After

hearing some of the music during a visit to

Massenet’s apartment in Paris, he wrote to

his friend and biographer, Maxim Gorki, that

the opera promised to be excellent. So great

was Chaliapin’s commitment that he spent

hours devising the correct hair and makeup

for his character. Arbell also went above the

call of duty, learning to play the guitar so she

could accompany herself in the Act Four aria.

Gunsbourg, meanwhile, devoted his time to

developing the stagecraft necessary to bring the

Illustration by Antonio Carnicero of

Don Quixote and Sancho encountering

the bandits, published in a 1947 edition

of the novel in Buenos Aires.

1950 illustration by Edy Legrand

of Don Quixote, mounted on his horse

Rocinante, and Sancho, on foot.