What most excited you when the

opportunity to direct

Carmen

was

presented to you?

I know the music so well (it was one of

the first operas I ever listened to). For

some reason, it’s become a part of the

soundtrack of many people’s lives. I

love the element of dance in it as well,

and how important that is in the piece.

Carmen dances as a seduction and as a

release. It’s rare in opera that dance is

central to a leading character. Having

started out as a choreographer, I'm

excited by that.

Can we talk about the updating

of the opera?

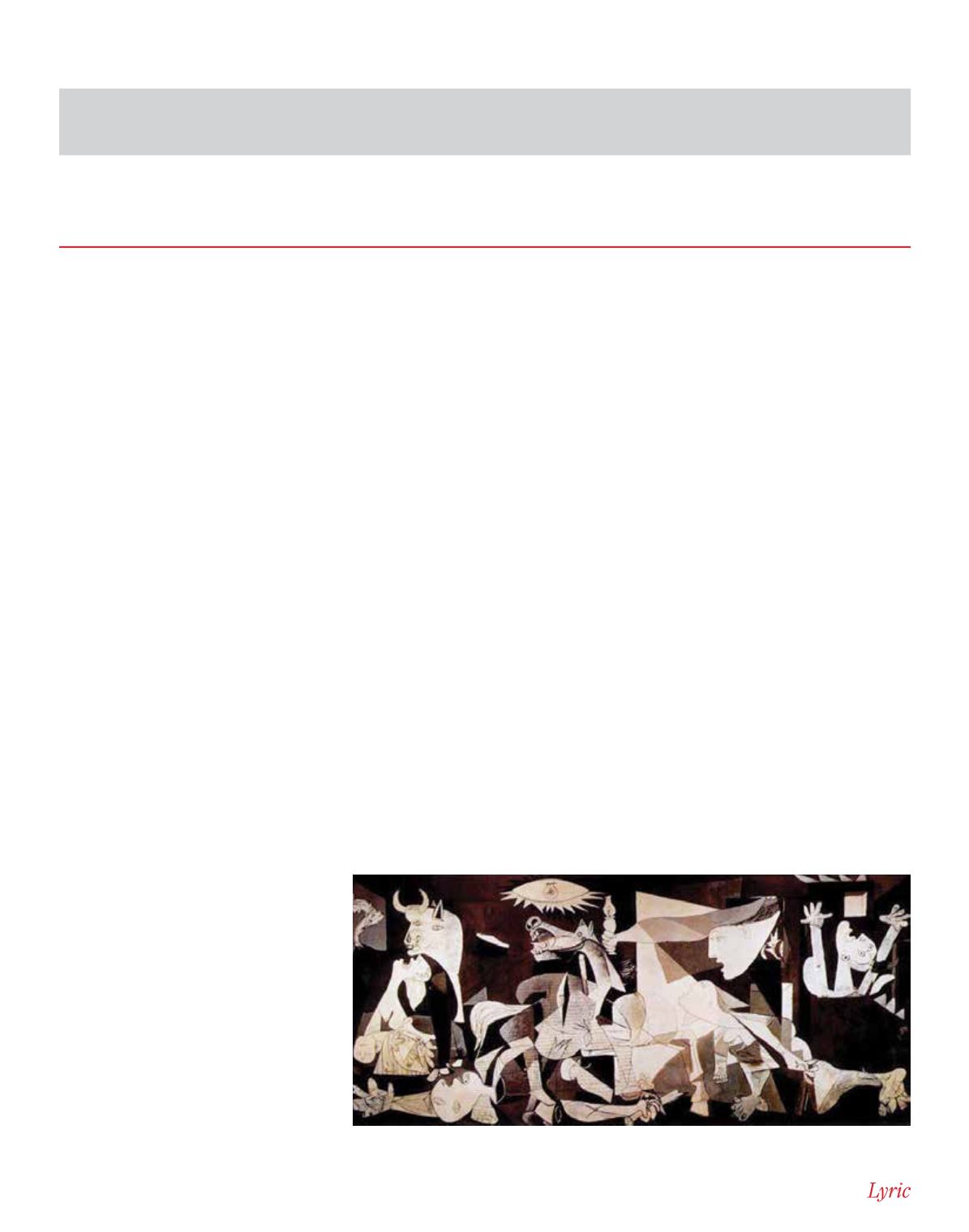

We moved it to 1936-37, during the

Spanish Civil War. One of my first

fascinations when approached about

Carmen

was the bullfighting element in

it. The most symbolic bull I could recall

was in Picasso’s “Guernica," created as

a reaction to the German bombing of

a small town during the war. There’s a

wonderful image in the upper left-hand

corner of a figure holding a dead child

or young woman in his arms, in total

grief and despair, and overlooking all

of that is this bull, just staring down

at it. It reminded me of the end of the

opera, with Carmen in the arms of

Don José, with him in such pain and so

tortured, and the idea of this bull and the

victorious Escamillo lurking above that

whole scene. I couldn’t get that image

from “Guernica” out of my mind.

I went to Madrid to see the painting,

and it became a jumping-off point for

the production. There was also the idea

of making the smugglers revolutionaries

in Act Three, with a cause they were

fighting for. That war was often described

as Fascism vs. Democracy – so it seemed

a good parallel for the opera.

34

|

February 11 - March 25, 2017

A Talk with the Director

Rob Ashford, director and choreographer of this season’s

Carmen

,

spoke with Lyric’s dramaturg, Roger Pines.

L Y R I C O P E R A O F C H I C A G O

MUSEO REINA SOFIA (MADRID)

Picasso's “Guernica” (1937), an important influence

on director-choreographer Rob Ashford’s response to

Carmen

.

At Lyric we have two different Carmens

bringing their own strengths to the role,

but what kind of characterization are

you most interested in seeing them

create onstage?

I’m hoping both ladies will see her

psychological and emotional journey

from the inside. She’s powerless within

society, yet completely empowered by

men’s reactions to her. She works in a

cigarette factory, so she’s quite low in

social standing. It's an interesting dance

she does between devotion and freedom,

between the possibility of true love and

striving for status – this is all fascinating

to present onstage.

What’s most intriguing to you about the

Don José/Carmen relationship?

I think it’s intriguing because he's a

“good boy” who does what his mother

and society want him to do. Even his

profession as a soldier is to protect and do

good, but he's fighting something inside

himself. There is a transference of his lust

for Carmen to his love for Carmen. He

leaves Micaëla, the good girl, and goes

for the baddest girl possible, and does it

with the same conviction that he courted

Micaëla! We have to examine exactly how

that conflict inside him drives him to do

what he does.

You're both director and choreographer.

This opera gives you crucial dance

sequences that open Act Two and Act

Four. What style of movement should

the audience expect?

There is a lot of partnering in this show,

and that’s intentional, because of the

intense relationship between Don José

and Carmen. They seem to dance around

each other through the entire opera, and

I thought we should mirror that in the

couples dancing onstage.

In Houston you used the recitatives, but

Lyric’s production will use the spoken

dialogue. How was the decision made to

go in that direction?

Anthony Freud felt strongly about using

the spoken dialogue, and [Houston

Grand Opera artistic director] Patrick

Summers felt equally as strongly about

the recitatives. I see the advantages to

both. How great that we get to try it a

different way, to see what that does to the

story – that’s exciting to me.