O P E R A N O T E S | L Y R I C O P E R A O F C H I C A G O

February 11 - March 25, 2017

|

33

animal-like temptress. An example of this

comes in the opera’s famed Act Three, in

which Carmen, reading cards, foresees

death for herself and for José:

If in the book of fate

your happiness is written,

then deal and have no fear,

for every card you turn,

to look into your future,

will show good fortune there.

But if you are to die,

the terrifying sentence

is written there on high [...]

the cards will show no mercy –

they still repeat: Death!

When Carmen comes to this

realization, beneath her the violins

start a plodding, dreadful rhythm that

they maintain for several measures.

Additionally, the orchestration of

Carmen’s premonition of death, with

its repetitive motions in the violins and

crescendo in the trombones, evokes the

Fate theme – a leitmotif in the Wagnerian

vein – that is first quoted in the overture.

The consistency of the underlying

orchestral gestures reveals a hidden turmoil

inside Carmen, something deep and

persistent. This underlying

distress

communicated

through Bizet’s music finds

no equivalent in Mérimée’s

Carmen who, in her final

confrontation with José, asserts, “You

want to kill me, I can see that, it is fated,

but you shall not make me submit.”

Mérimée’s Carmen has a tough interior

and exterior, even in dire moments. It’s

what builds her characterization as a

femme fatale, but Bizet’s interpretation

gives Carmen more complexity. This is

just one example of how Bizet leveraged

an aspect of Mérimée’s novella, the theme

of fate, and incorporated it into his opera.

While the novella expounds a steely

seductress, the opera’s heroine is more

enigmatic and three-dimensional. It was

Carmen who broke the mold and paved

the way for other psychologically layered

operatic heroines in the near future and

beyond. Massenet’s

Thaïs

(1881), the

story of a decadent Egyptian prostitute

transformed by her encounter with a

monk, comes to mind, as do the title

characters in Strauss’s

Salome

and Berg’s

Lulu

as equally complex heroines with

powerful sexual stigmas attached to each

of them.

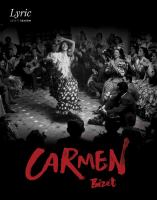

“Corrida” (1901), one of many memorable bullfight scenes painted by Pablo Picasso.

Though on its own, Mérimée’s

historically grounded novella hasn’t

equaled the success of Bizet’s passionate

opera, it’s only because Bizet’s work is

an extraordinary piece of music drama.

Bizet transformed an uneven pre-existing

source and imbued it with an augmented

dramatic intensity and an enchanting,

evocative melodic freshness.

Carmen

has

endured as the consummate operatic

masterpiece because its drama is as

memorable as its music.

Harry Rose has been writing critically about

opera and classical music since 2012 on

his blog, Opera Teen (operateen.wordpress.

com). He is also a blogger at the

Huffington

Post

and has had his writing published

by

The Washington Post

, in addition

to receiving mentions in

The New York

Times, The Christian Science Monitor

,

and on 105.9 WQXR. He is currently a

freshman studying Italian at Georgetown

University.

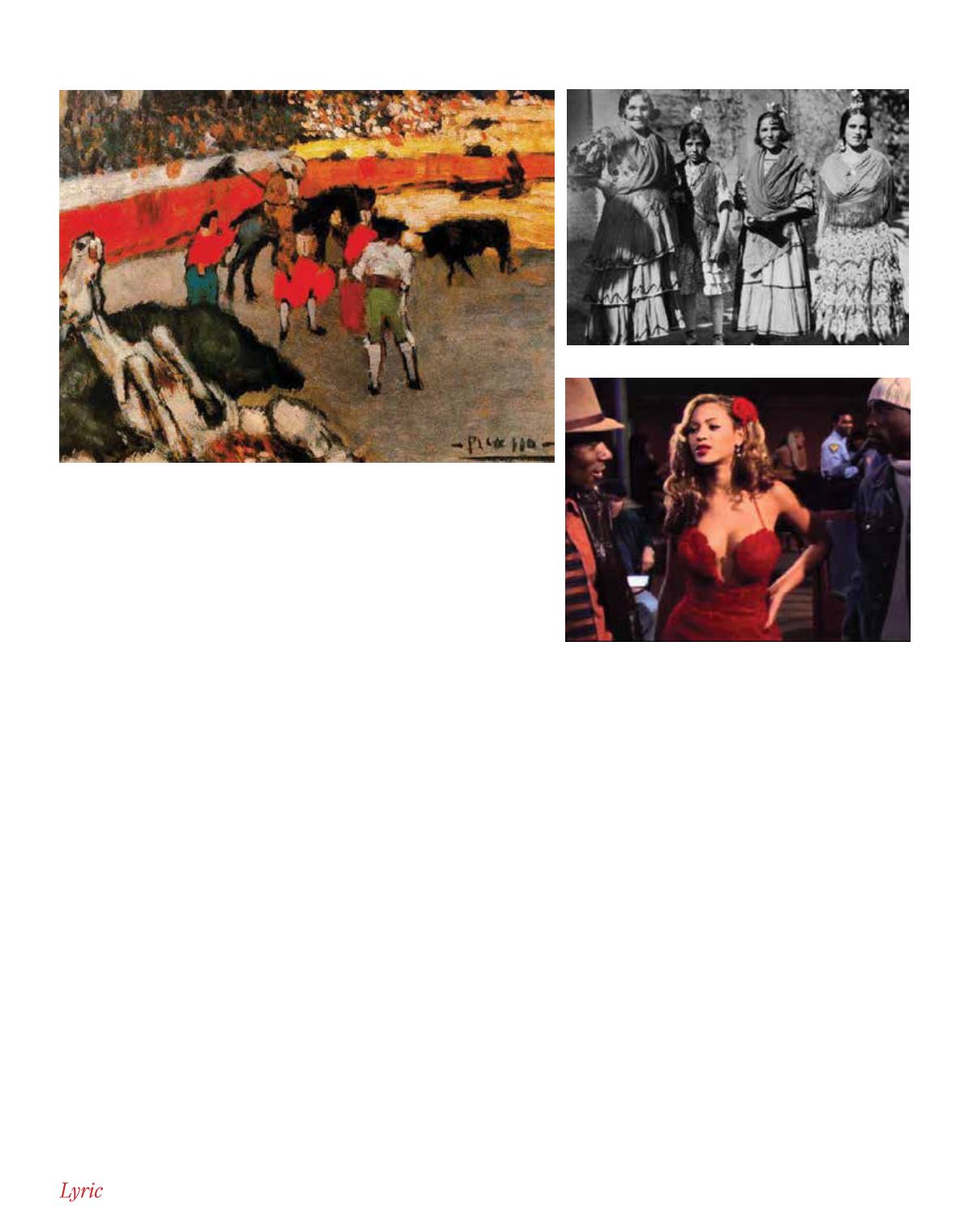

MTV’s contemporary take on the story,

Carmen: A Hip Hopera

(2001),

starred Beyoncé in her film acting debut.

Gypsies in Spain in the 1930s