O P E R A N O T E S | L Y R I C O P E R A O F C H I C A G O

32

|

February 11 - March 25, 2017

bourgeois family audience. Stories

with a moral, enhanced by light,

pleasant music, were the norm.

The Opéra also structured all the

works it commissioned similarly,

which, with spoken dialogue

in between set-pieces of music,

almost resembles modern musical

theater structure more than it

does traditional opera. Later revisions to

Carmen

included sung recitative in the

place of dialogue, but Lyric audiences will

see the Opéra Comique version that Bizet

and his librettists devised.

Bearing all this in mind, the creative

team for

Carmen

made some concessions.

The characters of Micaëla, Don José’s

virginal fiancée, and Frasquita and

Mercédès, Carmen’s lively friends, were

added. The librettists even considered

turning the smugglers, Dancaïre and

Remendado, into something approaching

comic figures. But as the opera’s evolution

progressed towards opening night, Bizet

became increasingly resolute about certain

unconventional details – he considered the

onstage murder absolutely indispensable

to the plot and the no-holds-barred acting

of the first Carmen, Célestine Galli-Marié,

adequately ferocious. Additionally, he

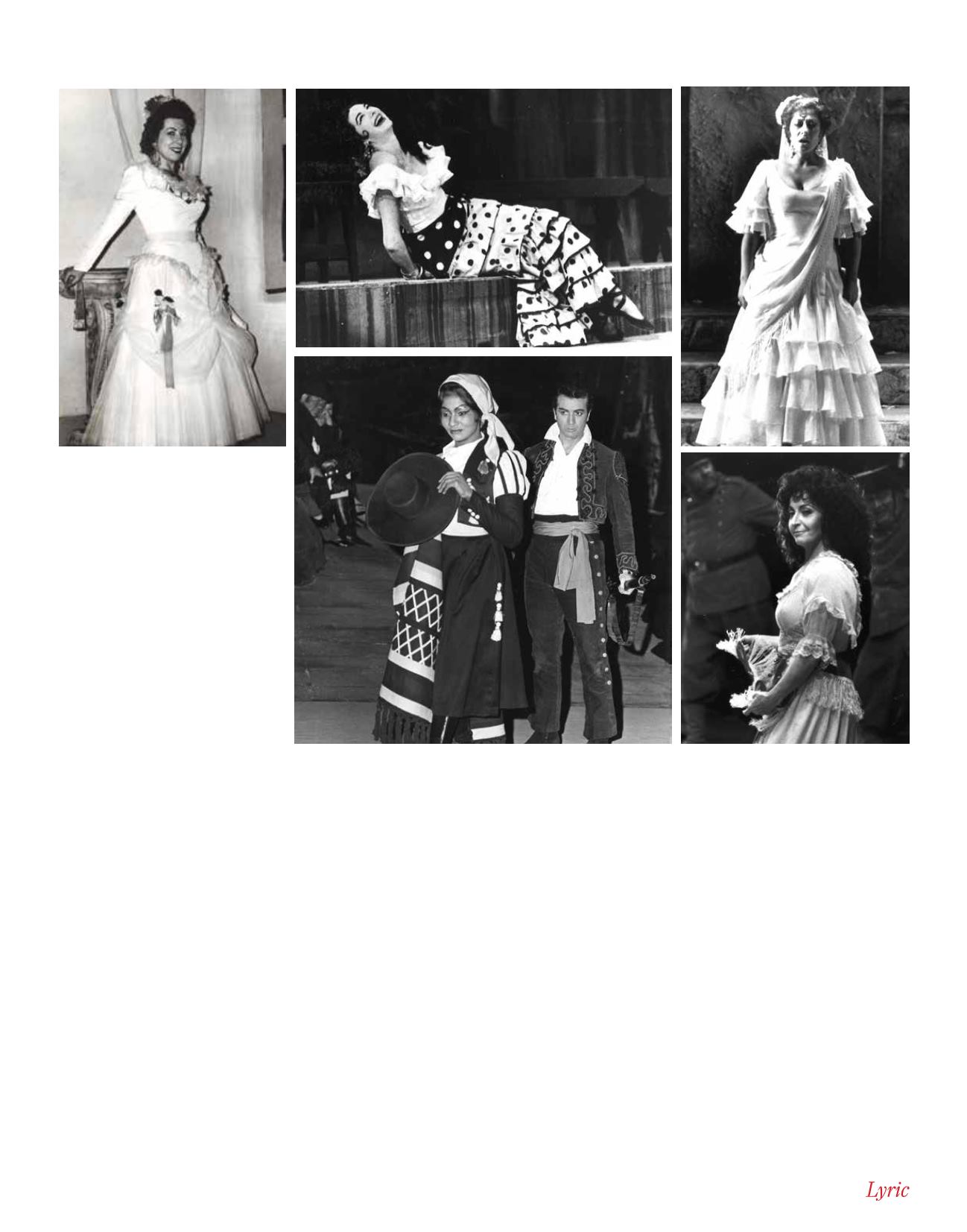

Among Lyric’s Carmens have been

(clockwise) the captivating Giulietta

Simionato, the ebullient Jean Madeira,

the fiery Alicia Nafé, the mesmerizing

Teresa Berganza, and the intense Grace

Bumbry (pictured with Franco Corelli).

insisted that the chorus, which previously

performed fixed on the sides of the stage,

move and act. The sensationalized media

coverage, plus the unapologetic onstage

depiction of a social class the elites saw as

dirty and lesser, contributed to one of the

biggest opening-night fiascos in operatic

history.

The initial acts were positively

received, but the audience became

increasingly hostile. “They did not seem

to want to enjoy themselves,” remarked

the singer Barnolt, who sang Remendado.

By the end, there were only a handful

of people left in the house when the

singers took their bows, and most of

the audience had dismissed the work

entirely. However, it wasn’t so much

Carmen’s outward sexuality or immoral

deeds that offended operagoers; it

was that the work represented a step

forward in entertainment at the time

– a step away from the customs that

distinguished French opera from what

was happening contemporaneously in

Italy (Verdi’s

Aida

and

Simon Boccanegra

)

and Germany (Wagner’s

Ring

cycle and

Parsifal

). In those countries, the medium

was arguably growing in a faster, more

innovative way towards Italy’s

verismo

and Wagner’s

Gesamtkunstwerk

. Maybe

Giacomo Puccini framed it best when

he contrasted his

Manon Lescaut

(1893)

with the quintessential opéra comique,

Manon

(1884)

,

by Bizet’s contemporary

Jules Massenet: “Massenet feels it as a

Frenchman, with powder and minuets. I

shall feel it as an Italian, with a desperate

passion.”

Carmen

embodied that

transition.

If anything, Bizet’s Carmen is a softer,

more sentimental creation than Mérimée’s

NANCY SORENSEN

NANCY SORENSEN

DAVID H. FISHMAN

TONY ROMANO

TONY ROMANO