O P E R A N O T E S | L Y R I C O P E R A O F C H I C A G O

30

|

February 11 - March 25, 2017

I

n

Carmen

Georges Bizet vividly depicted sun-soaked

Andalusia and its transient, adventurous gypsy inhabitants,

yet the composer created this work without ever setting foot

in Spain. It seems like a paradox that Bizet produced such an

adroit study of a regional culture and how certain personalities

worked within its confines without even coming into contact with

that culture! On another level, though,

Carmen

is just a result of

an artistic fascination with Spain, “exotic” gypsies, and nomadic

adventure that permeated contemporary Western Europe.

Yet what makes Bizet’s opera extraordinary is not that it

was able to put “authentic” Spanish flair onstage at Paris’s Opéra

Comique, but that it took a superficial cultural fascination

embodied in Prosper Mérimée’s 1845 novella of the same

name, highlighted its best moments, and drew realistic, multi-

dimensional characters out of it. Although audiences didn’t

immediately appreciate how Bizet brought Carmen

herself to

life, the opera’s initial shock value and the well-defined female

protagonists of the operatic stage who would follow Carmen

demonstrate good art’s intrinsic ability to provoke and stimulate

change.

Bizet’s chief source material was the novella of Mérimée,

the celebrated French author and historian. It appeared in the

Revue des Deux Mondes

in October 1845, with a fourth chapter

added in 1846. Mérimée probably first heard the Carmen story

from the Countess of Montijo (mother of Eugénie, the future

empress of France) while on his visit to Spain in 1830, but he

significantly embellished it when he finally put pen to paper. This

1830 visit, Mérimée’s first to the Iberian peninsula, included a

venture into the south where he studied the gypsies of Granada.

Though the culture fascinated him and served him well when he

wrote

Carmen

, Mérimée’s interest in the gypsies lay temporarily

dormant.

What apparently reawakened his interest was the continuing

publication of the writings of George Borrow, an English author

and contemporary of Mérimée who studied the Spanish gypsies

intensely. Mérimée himself was familiar with Borrow’s first

published book,

Le Zincali: An Account of the Gypsies of Spain

(1841), a comprehensive guide to the language, culture, and

customs of the gypsies of southern Spain. These peers didn’t share

an especially positive rapport, though. Indeed, Mérimée even

Novel Nomads: How a Fascination with Gypsies

Led to Opera’s Most Provocative Heroine

By Harry Rose

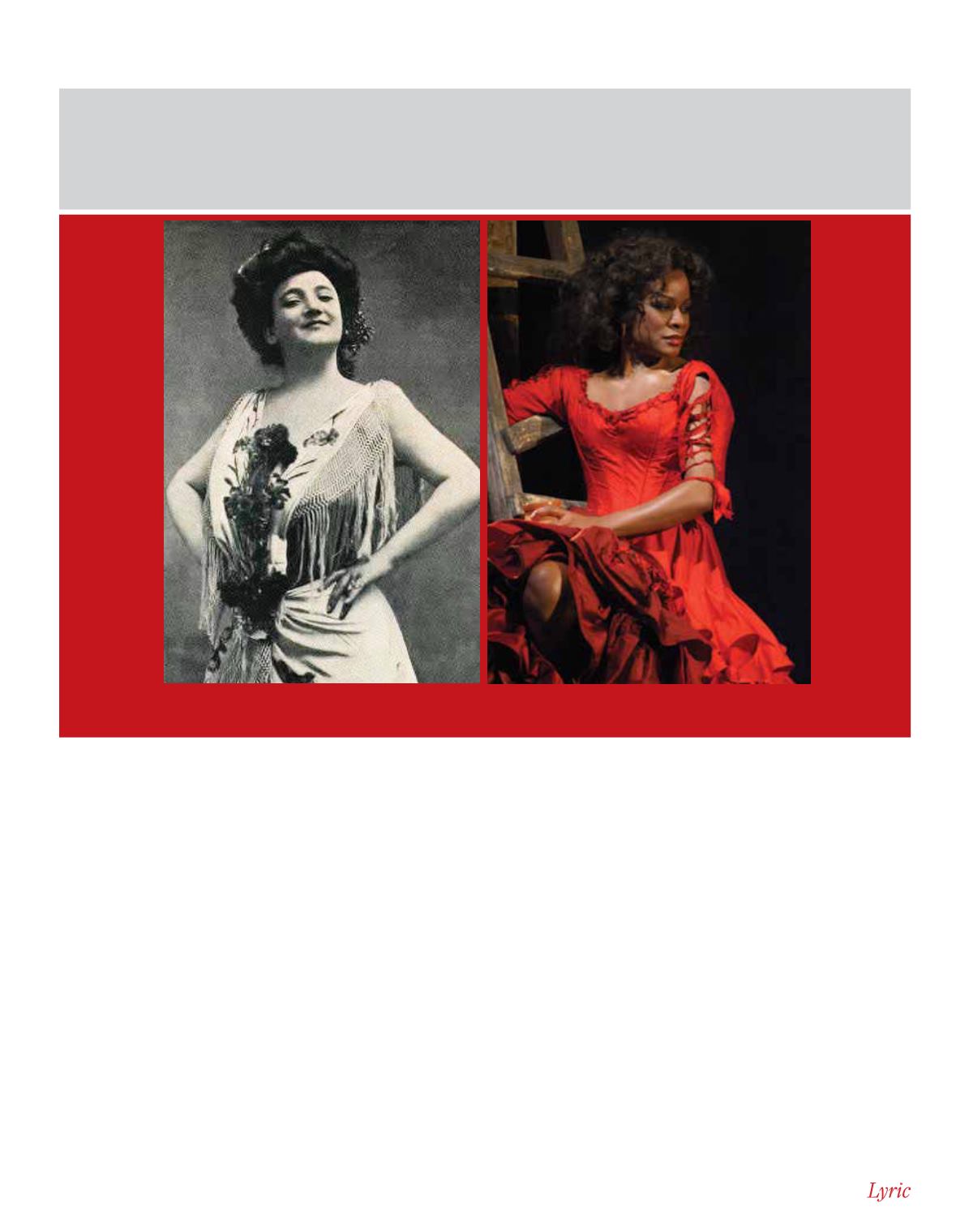

Two celebrated Carmens, a century apart: French soprano Emma Calvé and American mezzo-soprano Denyce Graves,

the latter pictured at Lyric in 2005.

DAN REST